Le consentement entre Claire et Jamie

Partie II : Le consentement silencieux

Par Fany Alice

Illustration : Gratianne Garcia

Autres textes qui pourraient vous plaire

Haut de page

Le consentement dans la saga Outlander se définit en bousculant les notions largement figées au XVIIIème siècle que sont le rapport au sexe, la discipline conjugale et l’infidélité.

C’est prioritairement dans la sphère intime qu’il focalise les critiques, tant il est attendu de manière répétée, par le biais d’une verbalisation sans équivoque. Or¸ on a pu voir (Partie I) qu’il est largement à l’œuvre dans les romans et s’inscrit dans une rhétorique du désir réciproque entre Claire et Jamie qui se découvrent pour apprendre à se donner un plaisir pur, intense, libre de toute censure et dans une désinhibition totale.

Le consentement silencieux est tout aussi essentiel que le consentement verbal, voire davantage, il est d’une exigence rare car il s’inscrit dans la capacité de donner, recevoir et interpréter des signaux sensoriels ou culturels. Surtout, il esquive la tentation moderne de ne pas partager grand-chose quand on partage un lit, tentation qui fait craindre un non consentement lors de l’acte sexuel quand l’écoute de l’univers sensuel et mental de l’autre est absente, fragile ou trop superficielle pour véritablement respecter son partenaire.

Ainsi, dans la sphère intime, le consentement silencieux est un langage des sens qui convoque une multiplicité de récepteurs sensoriels, la vue, l’ouïe, l’odorat, le toucher et même le goût, qui s’agitent, se croisent et se mêlent pour favoriser le lâcher prise, intensifier les sensations physiques, stimuler l’ardeur sexuelle. Il sous-tend le consentement verbal, le précède, le complète et l’accompagne au quotidien. Il nourrit l’envie de l’autre, permettant aux corps de se reconnaître d’emblée pour que le champ infini de tous les possibles s’ouvre à eux, sans avoir besoin des mots.

Dans la sphère publique, ce consentement silencieux ne se vit pas spontanément et devient même l’enjeu d’une âpre lutte entre Claire et Jamie. Il réclame une posture affective et une flexibilité mentale, véritable défi au quotidien, dans l’envie de s’ouvrir à la singularité de l’autre, comprendre son univers culturel pour lui faire une place aux côtés du sien, dans une recherche de compromis qui ne soit pas une compromission ou un reniement de soi mais bien une reconnaissance de l’autre comme l’égal de soi. On est au cœur de la dialectique qui consiste à se posséder mutuellement sans se déposséder de soi, à se mettre à la place de l’autre tout en restant soi-même, à trouver le chemin qui permet à chacun de s’épanouir en obtenant ce qu’il attend de l’autre sans qu’aucun ne soit jamais lésé, vaincu ou contraint.

Nombreux sont les couples du siècle de Claire qui s’érodent sur l’autel des réalités lorsque le monde de l’un et le monde de l’autre s’affrontent au point de rendre inatteignable la construction ou le maintien d’un pont, jonction entre le toi et le moi pour donner un sens au « nous ». A l’inverse, le XVIIIème siècle évacue cette question en organisant le couple sur un mode vertical où l’ascendant de l’un s’impose à l’autre, ce qui offre une stabilité certaine mais limite les potentialités pour devenir meilleur en apprenant de l’autre. En plaçant le bien-être mutuel au cœur de leur relation, le consentement entre Claire et Jamie autorise l’épanouissement personnel qui procure en retour à chacun la force nécessaire pour être toujours là l’un pour l’autre¸ dans une spirale vertueuse.

Ainsi, la violence conjugale exercée par Jamie sur Claire est le moment fatal où la dynamique du non consentement fondée sur le diptyque obéissance/discipline se fissure pour laisser place à ce nouvel équilibre né de l’écoute, du respect et de l’échange. Si Claire apparait comme la bénéficiaire immédiate de cette redistribution des rôles, protégée mais libre d’être elle-même, sans crainte disciplinaire, Jamie n’en est pas moins grandi, autorisé à partager ses attentes et à décharger ses tourments sur les épaules d’une femme sécurisée qui peut alors se donner entièrement, aimante, attentionnée, fidèle, sans que cela ne fasse de lui un homme faible.

Claire veut être protégée mais non contrainte, encore moins disciplinée. Jamie veut être aidé mais ne pas faire pitié, encore moins être dévirilisé : ainsi, s’enroule le consentement silencieux dans la sphère publique, gage de leur épanouissement mutuel.

Avant d’analyser comment le consentement silencieux se construit progressivement et douloureusement dans la sphère publique, voyons d’abord comment il s’articule dans la sphère intime.

Vue, ouïe, odorat, toucher et même goût lorsque l’on mordille la peau de l’être aimé : D. Gabaldon plonge le lecteur dans un véritable bain sensoriel. Tous les sens sont convoqués.

Tout au long des romans, l’attirance entre Claire et Jamie est entretenue par les odeurs rassurantes et familières qui deviennent des signaux sexuels motivants. Jamie a cette odeur musquée de lin et de fumier caractéristique du guerrier vivant au grand air avec cette légère transpiration masculine qui devient un véritable aphrodisiaque pour Claire.

Ils cherchent à créer un accord sensoriel hors norme, favorisant cette attraction animale qui les caractérise souvent où l’odeur, associée à la pilosité et au toucher, permet à Jamie de s’approprier Claire tel un fauve marquant son territoire : « Il frotta sa joue contre l'intérieur d'une cuisse, une jeune barbe féroce râpant la peau tendre. (…). Il a râpé l'autre côté, me faisant donner des coups de pied et me tortiller sauvagement pour m'éloigner, en vain. C'est ce que tu aurais dû faire avec moi, Sassenach. Tu aurais dû me frotter le visage entre tes jambes en premier » (Chapitre 17, T1 Le chardon et le tartan). Dans cette scène d’exploration et de découverte, on comprend qu’il faut du temps pour découvrir le corps de l’autre, pour apprendre à lui donner du plaisir et à en recevoir, et que cela passe par des expérimentations sans retenue.

Au chapitre 11 du tome 2, Le talisman, on a droit à cette scène cocasse où Jamie s’offusque des procédés dépilatoires et crèmes odorantes employés par Claire pour copier les parisiennes de la haute société. « Ça sent beaucoup moins, ai-je suggéré. Et qu'est-ce qui ne va pas avec ton odeur ? dit-il avec véhémence. Au moins, tu sentais une femme, pas un fichu jardin de fleurs. Que penses-tu que je suis, un homme ou un bourdon ? Voudrais-tu te laver, Sassenach, pour que je puisse m'approcher à moins de trois mètres de toi ? ». Le sens olfactif permet de s’approprier le corps de l’autre, de le garder en soi et de faire grandir le désir sexuel, toutes choses qui entretiendront la mémoire lors de la séparation forcée de vingt ans.

L’olfaction est un signal sexuel des plus explicites dans un chapitre du cinquième tome où Claire¸ en proie à des bouffées de chaleur nocturne d’origine hormonale¸ se retrouve sur le rebord de la fenêtre de Fraser’s Ridge à explorer avec Jamie leurs odeurs respectives nourrissant ainsi leur imaginaire érotique (Chapitre 109¸ T5 La croix de feu).

De même, le goût est souvent associé au fantasme de l’absorption dans un appel à la fusion maternelle pour prolonger l’unicité des corps : « Mes seins me faisaient mal et picotaient parfois sous les liens serrés de mes robes, voulant être allaités. Ses lèvres se refermèrent doucement sur un téton, et je gémis moi-même, me cambrant légèrement pour l'encourager à le prendre plus profondément dans la chaleur de sa bouche. Me laisseras-tu faire cela plus tard ? murmura-t-il avec une morsure douce. Quand l'enfant sera venu et que tes seins se rempliront de lait ? Me nourriras-tu aussi, alors, à côté de ton cœur ? (…). Toujours, murmurai-je » (Chapitre 13, T2 Le talisman).

Les bruits émis ont également un potentiel érotique. Claire y exprime toute sa féminité et son consentement¸ entre couinement¸ gémissement¸ halètement¸ souffle ou cri. Elle vocalise ainsi sa satisfaction dès la nuit de noces face à Jamie surpris mais rapidement ravi de constater le pouvoir de son corps sur la jouissance de sa partenaire : « Je me suis cambrée contre lui et j’ai crié. Il recula aussitôt (…). Je suis désolée dit-il, je ne voulais pas te blesser. Tu ne l’as pas fait. (…) Est-ce que ça arrive à chaque fois ? me demanda-t-il fasciné, une fois que je l’eus éclairé. (…). Non pas à chaque fois dis-je amusée. Seulement si l’homme est un bon amant » (Chapitre 15, T1 Le chardon et le tartan).

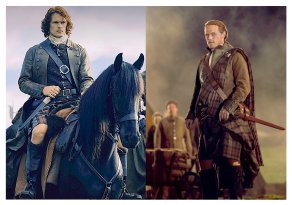

A. Malcom d’Edimbourg en 1766 : ils s’entendent avant de se voir.

La vue prend une dimension particulière lorsque Claire n’est plus dans l’insolente beauté de ses 27 ans mais approche de la cinquantaine et revient retrouver Jamie. Certes, elle se rassure préalablement auprès du regard masculin de son collègue et ami Joe Abernathy mais une pudeur intimidante l’envahit soudainement alors que Jamie reste muet en la contemplant nue lors de leurs retrouvailles, d’autant plus que lui ne semble guère affecté par l’âge. Il est finalement singulier de constater que le cheveu grisonnant, sans maquillage et vêtue des vêtements du XVIIIème siècle moins seyants que ceux, courts et ajustés, de la bourgeoisie bostonienne, Claire parait plus jeune et sans aucune perte de désirabilité aux côtés de Jamie que lors de ses années passées auprès de Frank. Le regard de Jamie sur Claire, et inversement, demeure constant pour souligner l’accord implicite de leurs pulsions respectives.

Parmi tous les sens, le toucher est sans doute le canal de transmission de référence de leurs émotions, celui qui crée le plus intensément cet espace d’intimité qui installe non seulement la connexion mais assoit le consentement dans la réciprocité. Il est à l’œuvre dès les premiers instants comme le rappelle Jamie dans le deuxième tome : « Tu n'as jamais reculé devant mon toucher dit-il (…). Pas même au début, alors que tu aurais pu le faire (…). Tu m'as tout donné dès la première fois; tu n'as rien retenu, ne m'as rien refusé de toi » (Chapitre 29)

Le toucher est omniprésent sous la plume de D. Gabaldon, d’abord professionnel et aseptisé, c’est le geste de Claire pour soigner. Il est aussi instantané que la vue lorsque Claire¸ fraichement débarquée en 1743¸ s’empare de l’épaule déboîtée de Jamie pour la réparer ; puis¸ il est contraint par la rudesse écossaise de deux pleines journées de chevauchées pour se prémunir du froid¸ de la pluie et de la faim en se lovant dans la promiscuité d’un tartan humide. Et il crée déjà une tension érotique entre Claire et Jamie qui se confirme alors qu’elle pleure Frank sur ses genoux (dans ses bras dans la série) à l’aube de leur arrivée au château de Leoch (chapitre 2, T1 Le chardon et le tartan).

Il devient un véritable langage silencieux entre eux une fois qu’ils sont mariés. Il est parfois le prélude à quelque chose de plus intense, comme une invitation à aller plus loin, ou il est juste autosuffisant, le moyen le plus immédiat pour lire l’état émotionnel de l’autre : « J'ai posé une main légère sur sa poitrine, non pas pour l'inviter, mais seulement parce que je voulais le sentir. Je connaissais ce besoin de toucher, de ne toucher que pour se rassurer que l'autre était bien là, présent en chair et en os » songe Claire en attente de réconfort (Chapitre 20¸ T6 La neige et la cendre) ; ou encore¸ à la fois sexuel et médical¸ il peut ramener à la vie alors que Jamie agonise après avoir été mordu par un serpent. Quelle que soit l’intention¸ ils tremblent au moindre contact, dans cette alchimie de température corporelle, le froid pour elle, la chaleur pour lui, recherchant l’apaisement de la chair. Ils tiennent leurs corps respectifs captifs, poussés par la force. Le corps de l’un a faim du corps de l’autre et enfermés ensemble, ils semblent au diapason.

Le toucher répare, connecte ou invite. Jamie est le premier à exprimer avec une simplicité touchante ce que déclenche en lui le contact avec Claire, ce mélange d’avidité lancinante et de douce plénitude qui rend si soudainement sa femme irremplaçable : « Même quand je viens de te quitter, je te veux tellement que ma poitrine se serre et mes doigts me font mal à force de vouloir te toucher à nouveau » (Chapitre 17, T1 Le chardon et le tartan). Invariablement, vingt ans plus tard, rien n’aura changé : « Je ne pouvais pas te regarder, Sassenach, et garder mes mains loin de toi, ni t'avoir près de moi, et ne pas te désirer » (Chapitre 26, T3, Le voyage).

Le toucher est non seulement indispensable mais il est inédit dans les sensations procurées. Alors que Jamie explique à Claire qu’il a déjà embrassé des filles, il ne peut ignorer que rien n’est comparable avec ce qu’il ressent à son contact : « Cela commence de la même manière, mais au bout d'un moment (…) c'est comme si j'avais une flamme vivante dans mes bras. Et je veux seulement m'y jeter et être consumé. » Jamie est à l’écoute du corps de Claire, jusque dans son cycle menstruel, il devine à chaque fois lorsqu’elle est enceinte, de Faith (Chapitre 41, T1 Le chardon et le tartan) et de Brianna (Chapitre 46, T2 Le talisman).

Claire est tout aussi saisie par l’intensité de son toucher : « Je pensais lui dire que son propre contact brûlait ma peau et remplissait mes veines de feu » (Chapitre 17, T1 Le chardon et le tartan). Mais au début de leur relation, elle est moins ouverte, effrayée par ce qu’elle perçoit déjà en elle comme n’étant pas un simple engouement pour ce corps aux lignes parfaites et à la sensualité si affirmée.

Le toucher impersonnel de l’infirmière se mue ainsi en désir de femme pour cette présence rassurante, cette étreinte ferme et confortable. Elle est irrésistiblement appelée vers cette silhouette droite et élancée, la courbe chaude de son épaule, la large pente de son dos, les veines ramifiées, la ligne de ses côtes ou le confort de sa poitrine¸ forgeant l’harmonie parfaite de leurs corps respectifs. Lovée dans la courbe de son corps, elle brûle devant son sourire rêveur, ses yeux intenses et plissés, ses joues hautes, sa bouche large et douce. Rassurée par le poids solide de son corps, le menton calé dans le creux de sa poitrine, elle espère ses mains sur les rondeurs de ses hanches pendant qu’elle laisse courir une main sous son kilt dans une succession de demandes silencieuses. Elle aime le sentir lisse, dur et avide contre elle, encore et encore.

Lorsque Jamie et Claire auront vaincu le secret de la possession mutuelle¸ après l’acte sexuel emblématique de réconciliation du premier tome¸ le toucher est le symbole de la fusion charnelle qu’ils cherchent sans cesse à revivre dans une illusion d’invulnérabilité : « Il souhaitait la couvrir de son corps, la posséder, car s'il pouvait le faire, il pourrait se dire qu'elle était en sécurité. En la recouvrant ainsi, unis en un seul corps, il pourrait la protéger. Ou c'est ce qu'il ressentait, même s'il savait que ce sentiment était insensé » (Chapitre 17¸ T5 La croix de feu).

D. Gabaldon décrit sans cesse cet appel irrépressible des corps, chaque scène s’inscrit dans la continuité de la précédente tout en y laissant malicieusement l’empreinte grivoise de la nouveauté, pour nous dire un peu plus quand on pensait déjà tout savoir. Ses récits sont tellement vivants qu’on croit entendre la fréquence cardiaque qui s’accélère et les pulsations libérées dans les corps.

Il n’est guère étonnant dès lors que le toucher soit autant convoqué pour les lier que pour les délier, lorsque la colère instaure une distance momentanée. « Ne me touche pas » dit Jamie furieux après la demande de Claire d’épargner Randall pour sauver Frank (Chapitre 21, T2 Le talisman). « Ne me touche pas » réplique Claire comme un écho lorsqu’elle découvre le mariage avec Laoghaire (Chapitre 35, T3 le voyage). Ils restent un mois sans se toucher lorsque le mensonge s’installe entre eux au sujet de Stephen Bonnet et de la bague en or récupérée par Brianna (Chapitre 53, T4 Les tambours de l’automne). Et que dire de cet instant où Jamie endormi confond Claire et Laoghaire et lui impose un toucher qui la révulse : « Rien d'autre ne pouvait expliquer la façon dont il m'avait touchée, avec un sentiment d'impatience douloureuse teinté de colère ; il ne m'avait jamais touchée de la sorte de toute sa vie » (Chapitre 101¸ T5 la croix de feu).

Le toucher est le lien qui engage ou désengage mais aussi le souvenir qui consume lorsque l’être aimé n’est plus là. Il faut que la chair le mémorise par une coupure en forme de J et de C laissée sur le pouce de l’autre au moment de la séparation, pour que le corps abrite le dernier vestige de l’être aimé. C’est tout naturellement devant les pierres, avant le départ de Claire, que tous les sens qui ont si bien contribué à nourrir le consentement sont assignés comme un épilogue glorieux mais tragique de ce bonheur finissant : toucher, bruits, odeurs¸ vue¸ goût… pas un ne manque… « Chaque contact (…) doit être savouré, remémoré, chéri comme un talisman contre un avenir vide de lui. J'ai touché chaque creux mou, les endroits cachés de son corps. Senti la grâce et la force de chaque os courbé, la merveille de ses muscles fermes (…). Goûté la sueur salée dans le creux de sa gorge, senti le musc chaud des cheveux entre ses jambes, la douceur de la bouche douce et large, goûtant légèrement la pomme séchée et le piquant amer des baies de genièvre. Tu es si belle, mon amour, me chuchota-t-il, touchant le glissement entre mes jambes, la peau tendre de l'intérieur de mes cuisses. (…). Il était dur dans ma main, si raide d'envie que mon toucher le faisait gémir d'un besoin proche de la douleur. (…). Il s'abandonnait à moi, et moi à lui, le désespoir se rapprochant de la passion, de sorte que l'écho de nos cris semblait s'éteindre lentement (…) » (chapitre 46, T2 Le talisman).

Pendant vingt ans, la mémoire sensorielle est alors vivace pour alimenter le souvenir : « Il pouvait jurer qu'il se réveillait parfois avec l'odeur d'elle sur lui, musquée et riche, piquée des senteurs vives et fraîches des feuilles et des herbes vertes » (Chapitre 4, T2 Le talisman). Et trop chargée de lui, Claire esquive le toucher de Frank tout comme Jamie s’enferme dans une abstinence entrecoupée de quelques instants de chair offerte mais non réclamée : la réparation avec Mary MacNab, le sacrifice avec Geneva, le devoir avec Laoghaire

Le toucher rétablit tout aussi aisément la connexion dans l’imprimerie d’Edimbourg, retissant le lien rompu devant les pierres vingt ans plus tôt : « Quand j'avais besoin de toi, je te voyais toujours, souriante, avec tes cheveux bouclés autour de ton visage. Mais tu ne parlais jamais. Et tu ne me touchais jamais. Je peux te toucher maintenant » (Chapitre 26, T3 Le voyage). Le toucher est de nouveau ce précieux sésame des permissions tacites. On se souvient, on restaure les habitudes, on réapprend le langage des corps qui était autrefois si familier : « Quand nous avions peur l'un de l'autre avant, murmurai-je, la nuit de nos noces, tu m'as tenu les mains. Tu as dit que ce serait plus facile si nous nous touchions » (Chapitre 26, T3 Le voyage).

Lors de leurs retrouvailles, Claire renoue avec l’excitation juvénile de ses premiers émois face à ce corps nu qui « [lui] a coupé le souffle. Il était toujours grand, bien sûr, et magnifiquement fait, les longs os de son corps lisses par le muscle, élégants par la force. Il brillait à la lueur des bougies, comme si la lumière venait de lui » (Chapitre 26, T3, le voyage). Elle est fébrile devant cette virilité piquante qui rend le corps de Jamie aussi accessible que le sien, comme si ses formes et courbes étranges étaient une extension soudaine de ses propres membres. Ils redécouvrent leurs corps respectifs¸ s’émerveillent de leurs courbes¸ décodent leurs secousses et pulsations¸ conscients de la respiration de l’autre¸ sensibles au moindre tressaillement… « C'est si bon d'avoir le corps d'un homme à toucher » s’émeut Claire¸ parcourant les nouvelles cicatrices¸ tandis que Jamie renoue avec la peau de velours blanc, pâle et enivrante¸ et les longues lignes du corps élancé de sa femme¸ tous deux « apprenant à nouveau en silence le langage de [leurs] corps » (Chapitre 34¸ T3 Le voyage).

Le consentement verbal qui s’exprime pendant l’acte sexuel, comme on a pu le voir en Partie I, est invariablement nourri de cette libre expression de petits bruits, odeurs, toucher qui stimule le côté pulsionnel de la sexualité et favorise le rapprochement physique : « Nous avons fait l'amour par consentement tacite, chacun voulant le refuge et le réconfort de la chair de l'autre » (Chapitre 25¸ T5 La croix de feu). Il est tout aussi explicite que le consentement verbal pour faire grimper l’excitation lors des rapports sexuels. Plus encore, l’écriture de D. Gabaldon montre à quel point le langage corporel est un révélateur précis de l’état d’esprit des deux partenaires réduisant finalement le consentement verbal à une presque banale évidence dès lors qu’on a tant pris soin d’être attentif au corps de l’autre. C’est là un élément essentiel de la singularité d’une relation où Claire et Jamie donnent plus d’une fois le sentiment de se dire tout¸ tout en restant muets

Paradoxalement, la problématique du consentement s’est cristallisée sur la sphère intime là où la sexualité est pourtant constamment éprise de réciprocité, mésestimant la sphère publique qui est le seul espace où s’abattent très vite et violemment les normes imposées, ne laissant que peu de place à l’expression libre.

Contraint par les mœurs de l’époque et douloureusement atteint par les événements du sauvetage à Fort William, Jamie est sommé d’asseoir son autorité de mari sur une épouse indisciplinée au caractère trop affirmé. Au XVIIIème siècle, la femme n’est pas réputée avoir d’opinion, elle est éduquée discrète et effacée pour apprendre à obéir à son époux. L’homme décide seul, sans souffrir d’être contesté, ne pouvant faire confiance aux femmes jugées trop instables et faibles, traçant des limites auprès de ses subordonnés, épouse, enfants, fermiers, colons¸ soldats…, assumant ses responsabilités au sein d’une société sévère qui ne manque pas de les lui rappeler.

Dans la sphère publique¸ le consentement entre Claire et Jamie fait sauter les digues qui figent les rôles, réclame le partage, abolit la subordination et permet à chacun de goûter à une liberté qui n’allait pas de soi : pour Claire, être elle-même, pour Jamie, être aidé. Comment tout ceci se met-il en place à partir de leurs violentes disputes consécutives au sauvetage de Fort William ?

C’est Claire qui souffre brutalement du non consentement lorsque s’abat sur elle la main punitive d’un Jamie au « visage austère de peur à la fenêtre de la chambre de Randall, tordu de rage au bord de la route, tendu de douleur face à mes insultes » (chapitre 22, T1 Le chardon et le tartan). Peur, rage, douleur : alchimie redoutable de trois sentiments explosifs débouchant sur une violence excessive (« Je perds rarement mon sang-froid, Sassenach, et je le regrette généralement quand je le fais ») et sadique (« Quant à mon plaisir (…). J'ai dit que je devrais te punir. Je n'ai pas dit que je n’allais pas en profiter »)[1].

Le consentement prioritairement établi est donc celui qui abolit toute violence conjugale. Jamie consent, non pas par rejet de cette pratique de son temps vécue par femmes et enfants comme l’ordre naturel des choses, mais parce qu’il découvre que Claire en ressort traumatisée et qu’il tient par-dessus tout à son bien-être. Il pense que la punition était méritée mais ne veut plus risquer de la blesser : dans le consentement¸ on préfère aimer l’autre plutôt qu’avoir raison.

Il sait également que l’ardeur sexuelle que Claire projette dans leurs ébats et qui le comble en retour ne peut se maintenir tant que pèse sur elle la menace de futurs coups. XVIIIème siècle ou pas¸ les règles qui régissent les hommes et les femmes ne peuvent s’appliquer à Claire. Jamie le sait et l’aime suffisamment pour se conformer à ses attentes. Il comprend qu’elle a besoin d’être sécurisée à tous égards¸ dans le rejet de toute violence mais aussi dans la revendication des sentiments¸ pour qu’elle

puisse lui faire totalement confiance : l’alliance et la promesse de fidélité complètent le serment et symbolisent tous trois le consentement nouvellement établi.

Claire est forte, elle peut se remettre de violences infiniment pires infligées par le monde extérieur, sauf que Jamie n’est déjà plus « le monde extérieur ». D’où ce tournant émotionnel particulier pour Claire¸ entre ce qu’elle est prête à offrir à leur couple et ce qu’elle entrevoit de la capacité de Jamie à évoluer¸ alors qu’ils cheminent pendant deux jours vers le château de Leoch au lendemain de la scène de violence conjugale (Chapitre 22¸ T1 Le chardon et le tartan).

Quant à Jamie¸ il observe Claire et décode des points clés de sa personnalité qui vont transformer une relation figée sur les attendus d’une époque en une relation consentie¸ se nourrissant de ses réponses laconiques et parcimonieuses pour mieux la comprendre et accepter son point de vue.

Fait inédit¸ celle qui ne craint pas les hommes craint Jamie, se méfiant de lui à trois reprises, au chapitre 22 (T1 Le chardon et le tartan), au début de leur chevauchée (« Il n'avait pas l'air particulièrement brutal à la lumière du lever de la demi-lune »), puis lorsqu’il réclame son poignard pour la prestation de serment (« Donne-le-moi. Comme j'hésitais, il dit avec impatience : Je ne vais pas l'utiliser contre toi. Donne-le-moi ! ») et enfin, au chapitre 23, dans leur chambre du château de Leoch (« Il se leva et posa les mains sur la boucle de sa ceinture. J'ai sursauté involontairement quand il l'a fait, et il l'a vu. (…). Non, dit-il sèchement, je n'ai pas l'intention de te battre. Je t’ai donné ma parole. »

Fait essentiel¸ Claire est dans l’état émotionnel des personnes à l’affut de la moindre gentillesse pouvant restaurer les repères perdus. Elle en vient à lâcher un pathétique « Tu me plais ! » à l’homme qui l’a battue la veille, quand il lui avoue que faire l’amour réclamait au préalable un sacrement divin. Certes, l’aveu est émouvant¸ dans l’esprit d’absolu de Jamie¸ mais la réaction enchantée, presque puérile de Claire interpelle à cet instant tragique de leur histoire. Jamie, comme le lecteur, est abasourdi, donne raison à Murtagh qui pense que les femmes sont incompréhensibles : insulté, griffé, bousculé lors du sauvetage de Fort William mais soudainement aimé après que « je t’ai battue à mort et (…) dit toutes les choses les plus humiliantes [qui] m’étaient arrivées. »

Mais, contrairement à ses contemporains, Jamie va non seulement chercher à comprendre mais y parvenir avec succès.

Il comprend que Claire va bien lorsqu’elle a le verbe haut et affirme son point de vue sans qu’on ne lui demande rien, quand elle jure, tempête, investit de passion avide le moindre sentiment. Or, à cet instant, elle est incohérente, éteinte, perdue, oscillant entre des moments d’abattement ou de béatitude et des rires hystériques. Elle est dans une soumission passive aux évènements qui ne lui ressemble pas, souffrant dans sa chair et dans son cœur face à ce « tendre amant » mais « perfide époux. »

Or, ce que Jamie aime en Claire, c’est son caractère entier et son assurance. Il loue son courage¸ appréciant qu’elle le défie (« J’étais en colère et tu m’as combattu férocement ») et son engagement impérieux pour ce qu’elle croit juste¸ admire sa résilience, respecte ses convictions, chérit son audace.

Confirmation est faite dans les tomes ultérieurs que Jamie ne se trompe pas sur la flamme qui maintient Claire épanouie et qui est désormais éteinte.

Ainsi, au deuxième tome, désemparé par l’attitude de sa femme enceinte aux prises avec nausées et malaises, il s’emporte pour s’en vouloir aussitôt, lui suggérant de l’envoyer promener. Avec un humour contemporain indécodable pour Jamie, elle lui lance alors : « Va directement en enfer. Ne passe pas par la case départ. Ne collecte pas les deux cents dollars. Là. Tu te sens mieux maintenant ? ». Et Jamie d’acquiescer car « quand tu commences à dire des bêtises, je sais que tu vas bien » (Chapitre 11, T2, Le talisman). De même, quand Jamie se montre autoritaire pour l’aider à expulser l’alliance coincée dans la gorge après l’agression de Stephen Bonnet¸ Claire s’agace et il est vite rassuré sur son état de santé : « Si tu te sens assez bien pour m'insulter, Sassenach, c’est que tu vas bien » (Chapitre 9¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne). Et lorsque Jamie est dans un état critique après la morsure du serpent¸ la placidité de Claire l’interpelle aussitôt « Tu me grondes toujours comme une mégère mais là que je suis désespéré, tu es douce comme un agneau » (Chapitre 93¸ T5 La croix de feu).

Tant que Claire crie et se révolte, Jamie peut donc conserver l’idée qu’elle s’investit dans le combat émotionnel de leur relation. Mais le silence que Claire installe à plusieurs reprises pendant qu’ils marchent vers le château de Leoch est inhabituel, obligeant Jamie à le briser à chaque fois. Il marque une rupture dans la complicité relationnelle, elle n’est ni avec lui, ni sans lui. Le mutisme est abandon, c’est une fuite qui crée une dangereuse distanciation.

Une première demi-heure de marche silencieuse est ainsi brisée par le récit de Jamie de ses propres humiliations punitives ; le second silence se rompt sur le douloureux souvenir du martyr qui le ronge depuis ses 19 ans et le pardon de Claire ; le troisième est suspendu par la demande de partager de nouveau son lit : il restaure alors sa dignité bafouée en la laissant décider et poser ses conditions, ce qu’elle fait, et qu’il accepte solennellement en prêtant serment¸ validant ainsi son point de vue (Chapitre 22, T1 Le chardon et le tartan).

Il faut garder à l’esprit que Jamie prend conscience que Claire est blessée par la punition corporelle avant de savoir qu’elle a d’autres mœurs d’une autre époque¸ et qu’elle ne s’est enfuie que pour retrouver un mari. Une fois la révélation faite¸ le regret s’ajoute au consentement. Rétrospectivement¸ le geste du serment est donc encore plus grand quand seul le bien-être de Claire¸ en dehors de toute autre connaissance¸ est l’unique motivation. L’emmener au-devant des pierres de Craig Na Dun pour lui permettre de rentrer chez elle achève de racheter la faute de Jamie dans une abnégation totale qui devient l’expression la plus achevée du consentement.

[1] La traduction française fait un contre sens en écrivant « J’ai dit que je devrais te punir. Je n’ai pas dit que j’allais en profiter ». Or, la phrase originale est bien : « I said I would have to punish you. I dit not say I wasna going to enjoy it », « wasna » étant la contraction de « was not » comme « dinna » (« I dinna ken ») est celle de « didn’t ». Quant à l’interprétation du « sadisme » de Jamie avec l’érection qu’il a dû avoir, certains pensent qu’il a eu du plaisir en la battant, d’autres qu’il était excité par ses fesses nues, l’écriture des romans étant régulièrement focalisée sur cette zone anatomique avantageuse de Claire et affolante pour Jamie. Le deuxième point de vue semble le plus juste¸ d’autant plus qu’il avoue avoir détesté lui faire mal mais ne pas pouvoir s’en empêcher par ailleurs. On retrouve là l’ambivalence émotionnelle d’un Jamie fortement dérouté par les événements¸ entre désir de punir et envie de chérir.

Dès lors¸ le consentement de Jamie a une incidence qui dépasse très largement le bannissement des violences conjugales. Il sanctuarise la personnalité de Claire, adoube ses choix et sa façon d’être, protège son univers mental et culturel. Il embrasse son caractère farouche et indépendant et lui permet de s’accomplir par elle-même, dans une liberté d’action l’autorisant à avoir une identité autre que celle de son mari, pour explorer une vie personnelle riche, sexuelle mais aussi professionnelle et sociale. En consentant à la libérer de l’obéissance et de son corollaire, la discipline, il lui offre la possibilité de s’affirmer sans crainte et de s’épanouir durablement.

Consentir à respecter et défendre l’univers mental de celle qu’on aime n’est évident pour aucun homme, d’aucune époque. Combien de femmes, aujourd’hui encore, se censurent, s’effacent ou se renient, cherchent à plaire plutôt qu’à se faire plaisir, par crainte de perdre un conjoint supposé incapable d’accepter ou d’évoluer ? Jamie offre à Claire le plus estimable des biens, celui d’être elle-même. Roger ne s’est pas trompé sur sa valeur : « Je ne sais pas qui tu étais, mon pote, murmura-t-il à l'Écossais invisible, mais tu devais être quelque chose pour la mériter » (Chapitre 13, T3 Le voyage).

Comme le consentement est une dynamique qui profite aux deux, dans la sphère intime comme dans la sphère publique, on peut dire qu’en l’élevant, Jamie s’élève avec elle, lui permettant en retour de bénéficier d’une « femme rare » qui, nourrie du soutien inconditionnel de Jamie, est suffisamment forte pour l’aider à devenir ce qu’il est.

Avant de regarder ce que Jamie gagne de cette nouvelle donne librement consentie, penchons-nous un instant sur les conséquences sur la vie de Claire.

Le moment où Jamie adoube l’univers mental et culturel de Claire commence avec le serment mais la confirmation officielle transparait surtout lorsqu’il déclame un fulminant « Je te crois » … « ton cœur » … « tes mots » … après le procès de sorcières, lorsqu’elle lui avoue venir du futur (chapitre 25, T1 Le chardon et le tartan). De retour dans son époque¸ en 1948¸ Frank est de suite dubitatif devant son récit et l’envoie voir un psychiatre. A l’inverse¸ le regard de Claire, magnifiquement capté par la caméra dans la série à cet instant précis où Jamie lui marque sa confiance, révèle le bouleversement intérieur que cette promesse éveille chez une femme trop habituée jusque-là à se penser seule et indépendante sans espoir d’être comprise.

Et¸ effectivement¸ plus qu’il ne la sauve physiquement¸ Jamie défend moralement ce qu’elle est face au monde extérieur¸ la présentant avec fierté comme étant une femme courageuse et une guérisseuse remarquable car « il avait depuis longtemps dépassé le point de remettre en question tout ce qu'elle faisait dans le sens de la guérison, que ce soit du cœur ou du corps » (Chapitre 23¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne). Il se vante de ses capacités de guérison à une époque où cette faculté est l’apanage des hommes¸ les femmes ne pouvant faire qu’usage de sorcellerie. Il montre une curiosité sans cesse renouvelée¸ à l’écoute de ses talents et de ses pensées¸ s’inspirant de son code moral¸ respectant scrupuleusement pendant vingt ans de séparation les habitudes nutritionnelles¸ de soin aux plantes ou de désinfection apprises auprès d’elle.

Cette relation renégociée par le consentement sur les décombres de la violence conjugale a aussi pour conséquence la transformation intime de Claire qui progresse sur le chemin de la connaissance et de l’acceptation de soi : avec Jamie, la protection n’est plus un aveu de faiblesse.

Le jeu d’actrice montre une évolution nette entre la première saison et les suivantes. Dès le début, on pressent dans l’attitude de Claire que l’indépendance, la maitrise, voire l’inaccessibilité la protègent de la perte d’estime de soi et des autres. Elle s’enferme dans un schéma de pensée consistant à refuser toute entrave et à ne dépendre de personne. Elle ne peut obéir car ne veut pas apparaitre faible : héritage de son histoire personnelle, renforcé par une époque, la seconde guerre mondiale, où il fallait être fort et invulnérable pour survivre… On connaît la jeunesse errante de Claire, le vide parental, la vie nomade auprès d’un oncle qui a sans doute davantage nourri son esprit que sécuriser son cœur.

« J'ai réalisé tout à coup pourquoi il voyait si clairement ce que Frank n'avait jamais vu du tout » avoue-t-elle (Chapitre 28, T3 Le voyage). En comparant Claire à un couteau « tranchant et méchant », mais « pas sans cœur », Jamie touche au plus juste. Il sait que Claire est une femme trop exceptionnelle, trop compétente, trop courageuse, trop belle pour ne pas s’attirer de solides inimitiés auprès d’hommes renvoyés à travers elle à leur propre médiocrité¸ l’obligeant à s’endurcir pour se protéger. L’amour de Jamie lui offre pour la première fois l’opportunité de baisser la garde et de faire confiance, d’accepter de ne pas tout maîtriser, pour se laisser guider par un homme protecteur et bienveillant qui chérit sincèrement ce qu’elle est. A la différence de Frank qui l’aime mais ne la comprend pas.

Elle peut prendre des risques émotionnels, accepter ses peurs et ses manques, que Jamie accueille sans que cela remette en cause sa farouche indépendance. « Je me sentais à la fois horriblement vulnérable et complètement en sécurité. Mais j'avais toujours ressenti cela avec Jamie Fraser » peut-elle enfin reconnaitre (Chapitre 9¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne) : ses faiblesses ne sont plus un fardeau menaçant pour son moral, son estime personnelle ou sa liberté, Jamie ne les utilisant pas pour la rabaisser ou la dominer mais pour la rassurer, lui donner confiance et la rendre plus forte, pas plus qu’il ne se sent lui-même en retour diminué par l’exceptionnalité de sa femme.

Intelligent, moral et loyal, Jamie a en effet les qualités requises pour s’engouffrer au travers des blessures d’abandon ou de trahison de Claire et lui apporter la sécurité affective dont elle a besoin mais qu’elle craint d’accepter. Car Jamie a perçu dès le début de leur histoire la faille qui forge une carapace entre Claire et le monde extérieur mais, jeune mari inexpérimenté et lui-même blessé par les événements de Fort William, il avait maladroitement cru que la violence et la soumission corrigeraient la situation. « Tu es habituée à penser par toi-même (…) tu n’as pas l’habitude de laisser un homme te dire quoi faire » lui avait-il dit avant de la punir avec sa ceinture (Chapitre 22, T1, Le chardon et le tartan). D. Gabaldon nous l’écrit : elle craignait de rester seule dans ce bosquet où il lui ordonna de se cacher¸ mais elle craignait encore plus de l’avouer. A ce moment de leur histoire, si la vulnérabilité de Jamie l’attire, la sienne lui fait peur ; et s’il est autoritaire¸ elle est forcément rebelle.

C’est par le serment¸ l’alliance et la fidélité qu’il s’attache durablement à Claire, et non par la contrainte, par cette fusion des corps et des âmes qui la rend libre de l’aimer et de lui faire confiance, de tout son être, et d'être aimée en retour avec une honnêteté qui correspond à la sienne. Claire est à même de recevoir la protection de Jamie parce que son emprise sur elle est tout aussi forte que l’emprise qu’elle a sur lui, l’un n’est plus en deçà de l’autre, ils sont inter dépendants dans le besoin. On sort ainsi de la verticalité de l’obéissance à sens unique pour tendre vers un va-et-vient égalitaire où¸ à tour de rôle¸ l’un s’en remet à l’autre dans la reconnaissance de la force de chacun : ici¸ c’est Claire qui consent à être protégée ; lภc‘est Jamie qui consent à être aidé.

Progressivement¸ les livres comme les saisons télévisées révèlent une femme plus sereine qui reconnait avoir peur¸ pleure¸ réclame l’affection de Jamie dans une spontanéité empreinte de fragilité et de tendresse et s’en remet à lui pour assurer leur survie dans une époque qu’il connaît bien et pour laquelle il est physiquement et mentalement mieux armé. Elle l’écoute¸ non pas par soumission mais par amour¸ jusque dans cette décision extrême de retourner vers Frank à l’aube de la bataille de Culloden¸ parce qu’elle sait que « sans le courage et l'intransigeance de Jamie », le pire lui serait arrivé, à Brianna et à elle (Chapitre 1¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne).

A partir de ces instants de réconciliation¸ Claire ne peut plus être sans lui¸ il ne peut l’être davantage sans elle¸ tant la possession mutuelle qu’ils érigent est devenue leur foyer sécurisé loin de toutes contingences matérielles (le terme « home » / « you are my home » … est récurrent dans les romans) : « C'est pour ça que j'ai si peur. Je ne veux pas être à nouveau la moitié d'une personne, je ne peux pas le supporter » peut-elle enfin reconnaître sans gêne (Chapitre 16¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne).

En acceptant ses faiblesses, Claire apprend à faire confiance et à s’en remettre à lui. Elle n’en aime que davantage Jamie parce qu’il sait la chercher dans ses besoins, ses espoirs ou ses attentes dont elle n'ose pas toujours parler et qui restent silencieux à l'intérieur d’elle. Il comprend son désir d’être utile¸ à l’hôpital des Anges¸ apaise ses doutes de ne pas être à la hauteur pour soigner¸ réparer¸ guérir. Il la soutient et l’encourage¸ embrasse avec elle son serment d’Hippocrate et son respect de la vie¸ partage son combat pour la pénicilline comme ses expériences médicales en matière d’autopsie. Elle peut se découvrir parce qu’elle s’attend à ce que les gestes de Jamie soient toujours prévisibles¸ c’est-à-dire rassurants. C’est l’absence de l’autre pendant vingt ans qui lui fait prendre conscience du tournant émotionnel que Jamie a su imprimer dans sa vie et qu’elle veut revivre : « Je n'avais été que moi-même avec lui, je lui avais donné une âme aussi bien qu'un corps, je l'avais laissé me voir nue, je lui avais fait confiance pour me voir en entier et chérir mes faiblesses, parce qu'il l'avait déjà fait » (Chapitre 36 T3 Le voyage). Lâcher prise¸ et pas seulement dans le domaine sexuel : c’est ce que Jamie lui offre par sa protection sans domination.

Finalement, Claire n’est jamais autant « obéissante » que lorsque la contrainte a disparu. Le lâcher prise est visible pour la première fois après les menaces du comte de Saint-Germain, lorsque les mots et la gestuelle de Claire s’unissent pour accepter la protection de son mari : « Ne t'inquiète pas, Sassenach, dit-il. Je peux prendre soin de moi. Et je peux aussi prendre soin de toi - et tu me le permettras. Il y avait un sourire dans sa voix, mais aussi une question, et j'ai hoché la tête, laissant ma tête retomber contre sa poitrine. Je te laisse, dis-je » (Chapitre 6, T2 Le talisman).

Claire s’habitue à cette bienveillance reposante qui ne peut faire défaut que dans des moments suffisamment exceptionnels pour qu’ils le notent tous deux, comme lorsque Claire subit des saignements pendant sa première grossesse : « Pour la première fois, je n'étais pas en sécurité dans ses bras, et cette connaissance nous terrifiait tous les deux » (Chapitre 22, T2 Le talisman).

Alors âgée de presque 50 ans¸ elle est toujours animée des mêmes urgences que dans sa jeunesse mais elle est néanmoins plus soucieuse de stabilité et désireuse de sérénité aux côtés d’un homme sur lequel elle peut compter : « Depuis le peu de temps où je suis revenue à lui, je m'étais à nouveau habituée à ce que Jamie sache toujours quoi faire, même dans les circonstances les plus difficiles » (Chapitre 40, T3 Le voyage). Qui aurait cru que la jeune femme qui, jadis, se braquait à la moindre injonction puisse un jour s’impatienter de l’absence de décision de celui qui est devenu son point d’ancrage face à n’importe quel vent trouble et menaçant ? : « Tu vas penser à quelque chose, dis-je misérablement. Tu le fais toujours. Il m'a jeté un regard étrange. Je n'avais pas réalisé que tu pensais que j'étais Dieu Tout-Puissant, Sassenach, dit-il enfin » (Chapitre 16, T4 Les tambours de l’automne).

La transformation de Claire en femme libre d’exprimer sa fragilité émotionnelle est encore plus saisissante lorsqu’elle retrouve Jamie vingt ans plus tard. Claire prend conscience à quel point sa liberté d’autrefois était orgueil et solitude et la détournait d’un bonheur authentique : « Et ce que j'avais pensé ma force - ma solitude, mon manque de liens - était ma faiblesse. (…). Et moi, si fier d'être autosuffisante à un moment donné, je ne pouvais plus supporter l'idée de la solitude » (Chapitre 16¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne). Elle est finalement encore plus libre dans la sécurité protectrice de Jamie.

Point d’orgue de cette vulnérabilité si touchante, cet instant lâché instinctivement comme une prise de conscience du caractère éphémère des choses que les scénaristes ont adapté dans le cadre de l’épisode « Les sauvages » de la quatrième saison lorsque les violences entre Indiens et colons allemands ont dévasté Claire : « J’ai peur. (…) Jamie tiens moi s’il te plait. Il me serra contre lui enroulant la cape autour de moi. Je tremblais même si l’air était encore chaud. J'ai peur que tu meures, et je ne peux pas le supporter, Jamie, je ne peux vraiment pas ! » (Chapitre 16, T4 Le tambours de l’automne).

Si on repense aux premières scènes de sexe entre Claire et Jamie avant la scène de réconciliation du premier tome¸ on perçoit subtilement chez Claire un doute quant à soi et une peur de l’abandon qu’elle dompte à travers une pratique sexuelle hyperactive¸ comme une échappatoire ou un moyen de combler par le sexe son besoin de fusion sincère par le sentiment. Avec Jamie¸ elle obtient les deux¸ fusion sexuelle et fusion sentimentale. Il est entreprenant là où Frank est exécutant¸ il exprime le désir intense de la vouloir encore et toujours quand Frank se laisse réclamer. Et Jamie veut tout : son corps¸ son cœur et son âme et lui donner la même chose en retour. C’est la juxtaposition des deux hommes qui aide Claire à prendre conscience que l’amour est risqué mais salutaire d'un point de vue émotionnel : elle consent à le laisser pleinement entrer dans son intimité parce qu’il ne se sert pas de ses faiblesses pour la dominer. Avec lui¸ elle n'a plus à retenir ses opinions, ses doutes¸ ses désirs ou ses préférences. Et sexuellement¸ il est toujours avide¸ la soulageant de ne pas avoir à être régulièrement en demande comme jadis avec Frank. Il est bien l’homme de sa vie¸ celui qu’il lui fallait.

La frontière entre la contrainte et le consentement reste néanmoins fragile comme le révèle cette dispute au quatrième tome¸ lorsque Claire reproche à Jamie de lui avoir caché l’état de santé du colon Byrnes pour l’empêcher de présider à sa mort et de se retrouver ainsi mêlée à un deuxième décès, après celui de l’esclave Rufus : « Mais tu ne peux pas décider de ce que je dois faire et où je dois aller sans même me consulter - je ne le supporterai pas, et tu le sais très bien ! » s’emporte Claire (Chapitre 13¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne). « Les gens te remarquent, Sassenach » rétorque Jamie... et cela a failli lui coûter la vie plus d’une fois. Claire sait la rapidité des déductions et la justesse des intuitions de Jamie, qui connait son monde et la méfiance des hommes envers les femmes trop libres. Cette « erreur » de Jamie est intéressante parce que rare dans la saga littéraire, c’est l’exception qui confirme la règle, à savoir que le tact¸ la douceur et la délicatesse sont des qualités bien à l’œuvre dans sa personnalité pour savoir protéger Claire sans la froisser ou qu’elle se sente diminuée.

Les moments où Claire ne peut se départir de sa nature rebelle¸ prenant des initiatives hasardeuses contre l’attente de Jamie, existent cependant. Mais D. Gabaldon montre comment le consentement qui s’est installé après la violence conjugale du premier tome modifie totalement la résolution des situations nées de la « désobéissance » de Claire. Les scènes décrites sont amusantes¸ en dépit du caractère tragique de l’instant¸ et utilisent un mécanisme littéraire de répétition des postures censé mettre en valeur l’alchimie parfaite entre deux êtres qui s’affrontent sans se faire de mal. Trois scènes se répètent ainsi sur un mode similaire de prise d’initiatives de Claire et de réaction autoritaire de Jamie : lorsque Claire est blessée après l’abordage des pirates (Chapitre 54¸ T3 Le voyage)¸ lors de l’attaque par Stephen Bonnet (Chapitre 9¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne) et après la disparition momentanée de Claire perdue dans la neige (Chapitre 23, T4 Les tambours de l’automne).

Le scénario commence invariablement par les reproches. Au chapitre 54 du troisième tome¸ le ton est donné d’emblée : « Maudite sois-tu, femme ! Tu ne feras jamais ce qu'on te dit ? Probablement pas, ai-je dit docilement ». Question rhétorique¸ Jamie connait la réponse… Au chapitre 9 du quatrième tome, Jamie est muet mais P’tit Ian se fait le porte-parole des pensées critiques de son oncle. Au chapitre 23, Jamie la tance sans ménagement : « Ne t’ai-je pas dit maintes et maintes fois de faire attention, surtout avec un nouveau cheval ? ».

Ensuite¸ on a plus ou moins la répétition du même déroulé où Claire est grondée¸ nettoyée¸ soignée¸ puis grondée¸ cajolée¸ dorlotée¸ bousculée¸ et de nouveau grondée¸ soignée, embrassée… Petite variante au chapitre 54 du troisième tome¸ elle est sur ses genoux nourrie à la cuillère de la main de Jamie. Autre petite variante¸ au chapitre 23 du quatrième tome¸ elle est également déshabillée et lavée de la tête aux pieds comme une enfant au point de gémir « avec une combinaison voluptueuse de douleur et de plaisir. » Et la fière chirurgienne Dr Randall aux quatorze années d’études semble bien heureuse ainsi infantilisée…

A chaque fois¸ Jamie laisse également libre cours à son fantasme de ce qu’il aimerait faire subir à Claire pour sa désobéissance ; l’attacher « face contre terre au-dessus d’un canon et [lui] avec un bout de corde dans la main » (!) au chapitre 54 du troisième tome ; ou encore, « sur un ton agréablement conversationnel, diverses choses qu'il aimerait me faire, en commençant par me frapper (…) avec un bâton » (Chapitre 23, T4 Les tambours de l’automne). Au chapitre 9 du quatrième tome, c’est sur un ton badin que P’tit Ian énumère les violences physiques dont son oncle est coutumier en cas de désobéissance, tout en étant certain qu’il n’en userait pas sur sa tante. Perspicace le jeune neveu…

Car ce qui diffère de la scène de violence conjugale du premier tome¸ c’est que la colère qui s’est avérée très mauvaise conseillère pour Jamie ce soir-lภest totalement évacuée. Comme le dit judicieusement Willoughby¸ Jamie « n’est pas en colère », il « a eu très peur » (Chapitre 54, T3 Le voyage). Et comme Jamie l’explique quelques temps plus tard à Claire¸ il est effrayé à l’idée qu’elle puisse se tuer par imprudence : « Fais-moi seulement une petite faveur, Sassenach. Essaie très fort de ne pas te faire tuer ou découper en morceaux, d'accord ? C'est dur pour la sensibilité d'un homme » (Chapitre 60, T3 le voyage). On retrouve cette même crainte au quatrième tome lorsque Jamie conclut : « Tu me fais peur, Sassenach, et ça me donne envie de te gronder, que tu le mérites ou non » (Chapitre 23, T4 Les tambours de l’automne).

Se dessine dans ces trois scènes un mode de résolution de leurs différends culturels homme/femme et XVIIIème/XXème siècle qui conserve un équilibre entre ce que chacun est prêt à accepter de l’autre. A Jamie, l’extériorisation de sa peur, dans une prise en main autoritaire mais consentie de sa femme où les velléités punitives restent à l’état de fantasme ; à Claire, la liberté de ne pas être inférieure à ce qu’elle est et de suivre son instinct de femme téméraire avec l’assurance d’avoir le soutien et le réconfort d’un époux compréhensif. Chacun va bout de l'expression de son point de vue sans qu'il y ait domination ou écrasement de l'un par l'autre. Le consentement est toujours aux aguets.

Si Jamie est parfois agacé par les initiatives de Claire, force est de constater qu’il le serait davantage si elle y renonçait. Car, quelle femme serait donc capable de se jeter sur les routes des Highlands pour le sauver de Wentworth, réparer son corps et son âme ? Lady Geneva, jeune oie blanche manipulatrice ? De sauter du Porpoise pour avertir son mari menacé d’arrestation ? Laoghaire, éternelle enfant qui n’aime Jamie que castré ? Certes, « je la retrouvais là où je l'avais laissée » constate Jamie. « Oh ? Et c'est le genre de femme que tu veux ? Le genre qui reste à sa place ? » (Chapitre 54, T3 Le voyage) demande Claire qui connait la réponse. Lorsqu’elle l’interroge sur la peur qu’il ressent pour elle, il a cette réplique sage qui montre qu’il prend sur lui par amour, ayant « vécu assez longtemps maintenant pour penser que ça n'a peut-être pas beaucoup d'importance, tant que je peux t'aimer » (Chapitre 56, T3 Le voyage). En cela, Jamie apparait bien comme un modèle de masculinité qui ne diminue pas face au charisme de Claire.

Voilà l’univers bienheureux qui s’offre à Claire lorsque Jamie consent à respecter sa personne en bannissant toute contrainte disciplinaire dans leur relation. Et qu’en est-il pour Jamie ? L’épanouissement de Claire suit une linéarité dans l’œuvre de D. Gabaldon qui rend ce personnage de plus en plus attachant au fur et à mesure qu’il exprime sa fragilité sans se départir de sa force. A l’inverse¸ Jamie est dès le départ placé très haut sur l’échelle du cœur¸ béni des Dieux¸ paré de toutes les grâces¸ avant que l’auteur ne le fasse chuter brutalement de son piédestal dans la violence conjugale¸ pour le faire renaitre de ses cendres tel un phénix.

Ce que les événements tragiques du sauvetage de Fort William révèlent sur la personnalité de Jamie réside dans ces deux besoins indissociables : protéger Claire mais aussi être aidé¸ ce qui est plus surprenant pour un homme de son siècle.

Lorsque Claire consent à être protégée sans que cela n’altère son indépendance ou la diminue dans sa propre estime d’elle-même¸ Jamie peut donner libre cours à ce qui offre un sens à une vie qui parait subie et éloignée de ses aspirations véritables. Cet aveu lancé en forme d’épitaphe alors qu’il s’apprête à renvoyer Claire dans son époque et à mourir sur la lande de Culloden¸ est un moment de lucidité sur une triste réalité dont on perçoit le désastre émotionnel sur une âme tourmentée : « Car j'ai menti, tué et volé; trahit et brisé la confiance. Mais il y a une chose qui doit peser dans la balance. Quand je me tiendrai devant Dieu, j'aurai une chose à dire, à peser contre le reste. Sa voix baissa, presque jusqu'à un murmure, et ses bras se resserrèrent autour de moi. Seigneur, vous m'avez donné une femme rare, et Dieu! Je l’ai aimée comme il faut » (Chapitre 46¸ T2 Le talisman).

Le besoin de protéger Claire s’est exprimé très vite¸ alors qu’ils se retrouvent au château de Leoch après s’être rencontrés à peine deux jours plus tôt : « Je t’ai désirée dès que je t’ai vue - mais je t’ai aimée quand tu as pleuré dans mes bras et que tu m'as laissé te réconforter, la première fois à Leoch » avoue-t-il à Lalllybroch (Chapitre 31¸ T1 Le chardon et le tartan). On note la demande impérieuse « tu m’as laissé... » que l’on retrouve après les menaces de Saint-Germain¸ « et tu me le permettras… ».

Ce besoin naît de l’amour mais aussi de la vulnérabilité refoulée qu’il perçoit en elle et qu’il désire libérer pour la prendre en charge. Cela signifie faire confiance à un homme qui a terriblement besoin de se sentir fort¸ admiré¸ aimé pour « une bonne » cause. Dans la notion de protection¸ on retrouve donc à la fois la garantie d’une préservation de l’intégrité physique de sa femme et la promesse, pour les deux, d’une élévation vers un mieux-être psychique. C’est cette dualité qui convainc Claire¸ d’autant plus qu’elle s’inscrit dans un engagement d’éternité que personne n’a pu (ses parents morts trop tôt ou l’oncle Lamb émotionnellement peu accessible) ou voulu (Frank et son intellectualisation distante du sentiment) lui offrir : le double sacrifice de Jamie pour sauver Claire¸ en offrant son corps à Randall à Wentworth¸ puis en la laissant repartir vers l’autre Randall le matin de la bataille de Culloden¸ est l’exemple le plus fort de la protection désintéressée dont il est capable par amour. Le cinquième tome révèle à quel point protéger Claire est une question existentielle pour lui¸ où la vie de celle qu’il aime est perpétuellement en jeu¸ lorsque Jamie¸ mordu par un serpent¸ livre ce qu’il pense être ses dernières volontés auprès de Roger. Le conjurant de la renvoyer dans son époque s’il n’est plus là pour elle¸ il a cette phrase énigmatique et lapidaire comme toute explication¸ aveu à la fois de l’exceptionnalité de sa femme et de l’énorme responsabilité qui est la sienne pour la préserver : « C'est une Ancienne, dit-il. Ils la tueront, s'ils le savent » (Chapitre 97¸ T5 La croix de feu).

Mais¸ dès les premiers temps de leur rencontre¸ Claire a aussi cette force morale hautement rassurante pour un jeune homme trahi¸ proscrit¸ manipulé jusque par ses oncles¸ contraint de dormir avec une dague sous son oreiller. Elle se détache de ceux qui gravitent autour de Jamie par son absence d’arrière-pensée utilitaire sur sa personne et par son amitié désintéressée. En retour¸ il est le seul à choisir de faire confiance à une Anglaise soupçonnée par tous d’être une espionne¸ ce qui ne peut que séduire une jeune femme lasse d’être seule et incomprise. On est frappés par ses confessions précoces – évasion de Fort William¸ (fausse) accusation de meurtre¸ récompense pour sa capture – qui pourraient facilement lui nuire mais on pressent déjà que le désir d’honnêteté avec Claire compte plus que sa propre vie. Et Claire a cette même soif d’absolu.

Avant le mariage et même après¸ jusqu’à la révélation sur la venue de Claire en 1743¸ leur attirance ressemble à un combat introspectif pour sonder la vérité de l’autre¸ faisant fi des intrigues politiques et des rivalités entre Ecossais et Anglais. De là vient leur capacité¸ qui ne se démentira jamais par la suite¸ à s’extraire de la fureur environnante des hommes et de l’Histoire pour savourer la quiétude du partage. Comme un puzzle¸ les pièces se mettent en place¸ entre le besoin de Claire d’être acceptée sans être jugée et celui de Jamie¸ d’être écouté et valorisé.

En effet¸ Jamie lui expose sans gêne son dos flagellé parce que Claire sait écouter et soigner sans le conforter dans un rôle victimaire¸ mais bien au contraire¸ pour l’aider à devenir plus fort. Claire a ce don de rendre simple ce qui est compliqué, évident ce qui est incertain. Il est touché par ce cœur résolument optimiste¸ porté à voir le meilleur en chacun et peu enclin aux rancœurs destructrices : le pardon de Claire après la violence conjugale n’est-il pas particulièrement empreint de grandeur d’âme ? Dès lors¸ Jamie n’a de cesse d’exprimer ce besoin irrépressible de se livrer au fil des pages des romans : « Mais je te parle comme je parle à ma propre âme, dit-il, me tournant pour lui faire face. Il tendit la main et prit ma joue en coupe, ses doigts légers sur ma tempe. Et, Sassenach, murmura-t-il, ton visage est mon cœur » (Chapitre 10¸ T2 Le talisman).

Lorsqu’une fois mariés et que la tension des rancœurs monte autant que celle des vérités à avouer¸ c’est Jamie¸ une fois encore¸ qui ouvre le premier la porte des secrets avec l’aveu de sa culpabilité quant à la mort de son père et le viol supposé de sa sœur par Randall¸ puis la crainte que le premier enfant de Jenny puisse être issu de ce viol¸ le fourbe Dougal ayant savamment entretenu la légende. Un aveu douloureux pour la fierté d’un grand guerrier qui s’ajoute à l’amertume de voir anéantis ses espoirs d’être innocenté par le déserteur anglais Horrocks quelques heures plus tôt : déception qu’il n’a eu le temps de partager avec Claire¸ se trouvant rapidement emporté vers Fort William puis dans une succession de violentes disputes avec elle. C’est dire si Jamie a besoin d’être écouté et aidé…

Parmi tout ce que Jamie comprend de Claire sur le chemin de leur réconciliation¸ figure cette dualité bien féminine : si elle est ravie par la grâce de ses muscles fermes ou la sensualité de ses étreintes, c’est néanmoins de sa vulnérabilité dont elle tombe amoureuse : « J'ai été plus touchée par les événements des dernières vingt-quatre heures, lorsqu'il m'a soudainement fait part de ses émotions et de sa vie personnelle, avec tous ses défauts » (Chapitre 22¸ T1 Le chardon et le tartan).

Claire consent à l’aider à combler son besoin instinctif de la protéger¸ de pourvoir à ses besoins et de la défendre. En cela¸ le guerrier écossais s’apaise, met de côté un caractère parfois rustre¸ et même grossier¸ pour se parer de douceur¸ de poésie et exprimer une personnalité plus nuancée qui accepte d’évoluer au contact de celle qu’il aime. Ce que Jamie gagne alors¸ c’est de pouvoir se réconcilier avec sa nature qu’il juge lui-même féroce et violente¸ c’est d’espérer que déteignent sur lui les innombrables vertus qu’il attribue à Claire¸ c’est de s’apaiser au contact de l’authenticité d’une femme sans fard ni faux-semblant.

Dans ces conditions¸ obtenir le consentement de Claire tant dans le domaine sexuel¸ par le plaisir qu’il lui procure¸ que dans la vie quotidienne¸ par les multiples attentions qui s’assurent de son bonheur personnel¸ est la condition même de son propre épanouissement.

L’écriture de D. Gabaldon est en effet sans détour : il ne peut être Jamie Fraser que lorsqu’il est avec elle. Avant de la connaître¸ il est Alexander MacTavish ou Jamie le Rouge¸ après son départ vers Frank¸ il redevient anonyme¸ le Dunbonnet¸ MacDubh¸ Alex MacKenzie ou Alexander Malcom¸ privé de celle qui fait sa force¸ contraint « de vivre vingt ans sans cœur (…). Vivre la moitié d'un homme, et s'habituer à vivre dans le peu qui reste, en comblant les fissures avec n’importe quel mortier qui sera utile » (Chapitre 35¸ T3 le voyage).

A partir de cet instant, Jamie guette les gémissements d’extase de Claire, l’expression de son visage, l’accélération de sa respiration, les contorsions de son corps quand elle se tortille sous son toucher, toutes ces marques de satisfaction et d’encouragement qui révèlent ce qu’elle désire. Rapport tendre ou rapport plus sauvage, Claire affiche un voyeurisme sexuel dans une ritualisation des gestes et des postures qui montre à Jamie qu’il est sur la bonne voie. Vision, toucher, audition, olfaction… Inlassablement réceptif aux mouvements de bassin de Claire, intime connaisseur de ses zones érogènes¸ il est toujours à l’écoute de Claire pour ancrer les corps dans le consentement : « J'ai pensé à ces petits sons tendres que tu fais quand je te fais l’amour, et je pouvais te sentir là à côté de moi dans le noir, respirant doucement puis plus vite, et le petit grognement que tu fais quand je te prends pour la première fois, comme si tu t’attelais à la tâche » (Chapitre 41, T1 le chardon et le tartan).

Sur le bateau qui les emporte de retour vers l’Ecosse au troisième tome¸ Jamie se livre à une véritable exégèse des vocalises de Claire. Le moment est drôle¸ c’est une belle scène de décryptage du consentement par l’écoute des sons du corps féminin ainsi mise en scène par la série. « Et nous verrons quel genre de bruit tu ne fais pas, Sassenach » conclut Jamie parfaitement au fait des petites habitudes érotiques de sa femme (Chapitre 52¸ T3 Le voyage). La voix et l’ouïe sont d’ailleurs les deux premiers sens en action qui réveillent leurs mémoires charnelles lorsque Claire pousse la porte de l’imprimerie

Dessin de Silvia Mesas.G Dessin de Silvia Mesas.G

Ainsi¸ Claire le laisse assurer leur avenir à Fraser’s Ridge¸ lui fait confiance « sur sa vie » et « avec son cœur », « pour toujours » (Chapitre 19¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne) afin de bâtir leur maison et organiser leur vie. A chaque fois que Jamie lui intime délicatement l’ordre de l’attendre, de s’éloigner¸ de faire attention ou de le laisser faire, on ne voit plus une femme dominée et un homme dominateur mais plus prosaïquement, un être humain en demande et un autre qui prend les choses en main.

Il ne peut trouver un semblant de quiétude intérieure que s’il se trouve des protections de substitution : Fergus et sa main coupée¸ la famille de Jenny et les fermiers affamés¸ les hommes d’Ardsmuir et enfin Willie. Ce qui signifie aussi que lorsque Claire n’occupe pas tout l’espace de sa vie¸ il est influençable. On a vu le pouvoir de Dougal sur lui¸ l’exhibant dos nu devant les villageois écossais pour engranger les soutiens et les deniers¸ lui choisissant une épouse pour ensuite lui intimer l’ordre de rester dans une retenue émotionnelle avec elle et de la battre pour désobéissance. Après le départ de Claire¸ c’est Jenny qui sait arrimer son frère à ses propres priorités¸ tramant un mariage avec Laoghaire qu’elle sait elle-même condamné à l’échec. La peur de la solitude le contraint à accepter et Claire pardonne parce qu’elle connait ses manques¸ « parce que tu es un honnête homme, Jamie Fraser, ai-je dit en souriant pour ne pas pleurer. Et que le Seigneur ait pitié de toi pour ça (Chapitre 59¸ T3 Le voyage).

Ces vies vécues sans elle restent néanmoins factices¸ artificielles en comparaison de la vie avec Claire. Car en la protégeant¸ c’est aussi lui-même qu’il protège¸ en projetant dans leur couple leurs espérances de bonheur et de vie meilleure. Dans sa relation avec Claire¸ on retrouve l’affirmation expiatoire qu’il peut être un homme bon. Elle est en quelque sorte sa rédemption. Ce n’est pas un vain mot pour un homme croyant qui se questionne sur le fond de son âme. Et c’est en s’ouvrant à Claire qu’il parvient à établir ce lien de confiance où chacun se laisse guider par l’autre afin d’apaiser - et chérir - leurs zones de fragilité respectives.

Jamie se pense violent et en ressent un malaise coupable. Bien qu’il soit violent par nécessité et non par choix¸ encore moins par plaisir¸ il a une haute estime de la valeur d’un honnête homme et craint de ne pas en être digne : « Et je me suis souvent demandé si j'étais maître dans mon âme, ou si j'étais devenu l'esclave de ma propre lame. J'ai pensé maintes et maintes fois, continua-t-il en regardant nos mains liées¸ que j'avais tiré ma lame trop souvent, et passé si longtemps au service de la lutte que je n'étais plus apte aux rapports humains » (Chapitre 28¸ T3 Le voyage). Au tome suivant¸ les interrogations reviennent avec la même urgence angoissée : « Tu es le meilleur homme que je n'ai jamais rencontré. Penses-tu vraiment que je suis un homme bon ? Je suis un homme violent, et je le sais bien, même quand elles sont faites par la plus urgente nécessité, de telles choses ne laissent-elles pas une marque sur l'âme ? » (Chapitre 13¸ T4 les Tambours de l’automne).

Il est vrai que frapper Claire sans penser un instant à ce qu’elle ressent après son enlèvement¸ n’a pu qu’inciter le lecteur à réviser son jugement sur Jamie ou¸ tout au moins¸ à s’interroger sur la valeur de cet homme. Son attitude violente a révélé à quel point Jamie est obsédé par le danger¸ sur ses gardes¸ les nerfs à vif¸ préférant le pire¸ l’agressivité verbale et physique sur celle qu’il aime¸ plutôt que d’apprendre à vivre avec la menace. Claire¸ ancienne infirmière de guerre¸ se retrouve face à un cas de stress post traumatique qui touche bon nombre de soldats. Mais quelle vie peut donc espérer Jamie lorsqu’il est sans cesse nerveux¸ compensant ses peurs par une possessivité malsaine sur Claire¸ prêt à lui imposer continuellement son autorité même en l’absence de danger pourvu qu’il se donne l’illusion d’évacuer tout risque ?

Le moment où Claire¸ dans la chambre du château de Leoch¸ compare Jamie à Black Jack Randall dans une ultime saillie pour qu’il cesse ses velléités de la prendre de force¸ est essentiel (Chapitre 23¸ T1 Le chardon et le tartan). De toutes les insultes proférées par Claire¸ celle-ci est véritablement salutaire et attendue. D’abord¸ parce qu’elle stoppe cette agaçante spirale des brutalités sur Claire depuis Fort William – à cet instant-là mais aussi définitivement dans l’œuvre de D. Gabaldon - car Jamie veut l’estime et l’amour de Claire¸ mais ensuite¸ parce qu’elle désigne la ligne de front où se situe le combat de Claire à mi-chemin entre la médecine et l’amour pour aider Jamie. Depuis ce moment¸ les interrogations de Jamie tournent inlassablement autour de cette fragile frontière entre monstres et héros (qui donne son titre à l’épisode 9 de la cinquième saison)¸ dans le regard que Claire lui renvoie et qui représente sa boussole et sa conscience.

Pire¸ Jamie est rongé par une pensée obsessionnelle selon laquelle il porte malheur à ceux qui l’approchent. Il l’avoue à Claire¸ dans le troisième tome¸ mais cette angoisse est déjà installée lors du sauvetage de Fort William¸ dans la crainte que Claire puisse suivre les traces de son père ou de Jenny entre les mains de Randall. « Trop de gens sont morts, Sassenach, parce qu'ils me connaissaient - ou ont souffert de me connaître. Je donnerais mon propre corps pour t’épargner un instant de souffrance - et pourtant je pourrais souhaiter fermer ma main à l'instant, pour t’entendre crier et être sûr que je ne t’ai pas tuée, toi aussi » (Chapitre 54¸T3 Le voyage). N’est-ce pas exactement ce qu’il a fait ? Claire sauvée dans une prise de risque inouïe¸ à mains nues et pistolet déchargé¸ puis Claire battue¸ criant suffisamment fort pour sa sinistre assurance (et pas seulement pour que les hommes du clan obtiennent satisfaction) ?

D. Gabaldon dissémine parfois des clés de lecture dans les pages¸ voire les tomes¸ qui suivent un événement : qu’il s’agisse de celui-ci ou de la scène de sexe des retrouvailles du troisième tome en miroir de celle de réconciliation du premier autour de la problématique du sexe sauvage (« Je ne peux pas être doux » T1 - « Ne sois pas doux » T3)¸ des explications de Jamie dans les sources chaudes après Wentworth sur ce qu’il a parfaitement compris des attentes sexuelles de Claire (Chapitre 41¸ T1 Le chardon et le tartan) ou des scènes fondées sur un mécanisme de répétition… On comprend ainsi que le consentement est une dynamique qui demande beaucoup d’écoute du besoin de l’autre¸ de compréhension et de patience mais là résident non seulement l’épanouissement mutuel mais les ressorts de la durabilité d’un couple.

Dès lors¸ Claire aide Jamie à évoluer de la possession vers la protection¸ de l’autorité vers la bienveillance¸ et finalement d’une souffrance subie à une souffrance vaincue. Le sauvetage de Wentworth et les confessions auprès du Père Anselme sont le prélude à une réflexion sur le sens de la souffrance (dans une posture quasi christique pour Jamie et non moins spirituelle pour Claire) et la signification de leur rencontre si improbable qui les relie de manière indéfectible pour construire quelque chose de beau¸ de pur et d’intense qui rachète les péchés de Jamie.

Claire transforme progressivement le combat de Jamie contre Randall¸ ce n’est plus une vengeance destructrice pour laver un honneur bafoué mais une affirmation de la valeur de la vie¸ celle de Claire¸ dont la défense impérieuse habille de noblesse une bataille qui n’en avait pas. Jamie tue Randall parce qu’il est sur sa route¸ sur la lande de Culloden¸ et non plus dans un périple obsessionnel et coûteux qui a déjà entrainé la perte d’un bébé¸ l’arrestation de Jamie¸ le viol de Claire pour sa libération. Jamie est dans une attitude similaire de saine distanciation lorsqu’il tente d’aider sa propre fille¸ Brianna¸ dans sa reconstruction après le viol par Stephen Bonnet ; ce qu’il ne parvient pas à obtenir de Murtagh¸ dans la version télévisée¸ qui n’est sauvé par aucun amour¸ pas même celui de Jocasta¸ enfermé dans une pulsion destructrice où la lutte armée est devenue une fin en soi qui ne peut que l’engloutir avec elle.

La série instaure une bénédiction rituelle de Claire envers son « soldier » lorsque celui-ci part à la guerre¸ lui offrant l’assurance que le sang qu’il va fatalement verser ne saurait corrompre son âme. Ces instants montrent aussi que si Claire risque de le perdre physiquement, elle sait ce qui est important pour Jamie et prend sur elle par amour. De même¸ au cours de la cinquième saison¸ la série opte pour une démonstration simplificatrice (c’est parfois là son principal défaut) en inventant de toutes pièces le personnage du lieutenant Knox tué de sang-froid par Jamie mais non sans conscience¸ pour nous expliquer¸ s’il en était besoin¸ que les actes de Jamie ne sont jamais gratuits mais dédiés à la protection de ceux qu’il aime. Knox épargné et Jamie arrêté et ce sont Fraser’s Ridge confisqué¸ Claire veuve¸ les enfants déshonorés et les colons expropriés.

Claire est là pour lui faire comprendre que si ses actes ne sont pas toujours exempts de tout reproche¸ ils ne sont jamais faciles et toujours guidés par la survie de ceux qui comptent sur lui¸ et elle est à ses côtés pour porter avec lui la solitude née de la responsabilité et du pouvoir : « Tais-toi. Jamie, as-tu déjà fait quelque chose pour toi seul – sans penser à quelqu'un d'autre ? » (Chapitre 40¸ T3 Le voyage)

Un instant de complicité du cinquième tome résume cet état de parfaite connivence dans la réparation des blessures¸ en rappelant au passage que l’entraide¸ comme le plaisir sexuel qu’ils se donnent¸ est toujours un consentement réciproque : « Sais-tu que le seul moment où je ne souffre pas est dans ton lit, Sassenach ? Quand je te prends, quand je suis dans tes bras, mes blessures sont guéries, et mes cicatrices oubliées. Je soupirai et posai ma tête dans la courbe de son épaule. Ma cuisse pressait la sienne, la douceur de ma chair étant un moule pour sa forme plus dure. Les miennes aussi » (Chapitre 87¸ T5 La croix de feu). Il est d’une franchise absolue avec elle¸ même si cela agace parfois (comme l’aveu de son plaisir éprouvé en pleine violence conjugale) car le don de soi ne survit pas à la malhonnêteté ou au mensonge : « Il n'y a que deux personnes dans ce monde à qui je ne mentirais jamais, Sassenach, dit-il doucement. Tu es l'une d'entre elles. Et je suis l'autre » (Chapitre 21¸ T6 la neige et la cendre).

Au fil des pages et des romans¸ Claire est ainsi fidèle à la métamorphose entamée après le serment¸ sentimentalement pleine et entière dans le soutien et l’encouragement¸ en femme sereine dont le don de soi est désormais tout autant charnel qu’émotionnel : « Je ne peux pas te voir comme une brute, dis-je. (…) Je le sais, Sassenach. Et c'est parce que tu ne peux pas me voir ainsi que cela me donne de l'espoir. Car je le suis – et je le sais – et pourtant peut-être… Il s'interrompit, me regardant attentivement. Tu as ça… la force. Tu l'as, mais une âme également. Alors peut-être que la mienne sera sauvée » (Chapitre 28¸ T3 Le voyage). Si Jamie pressent qu’elle lui ressemble mais en mieux¸ est-ce parce que Claire guérit et sauve des vies ? Comme si elle était une émanation de lui¸ son âme sœur¸ mais en plus parfaite ? C’est ce qui ressort des romans comme de la série¸ dans cette perception que la valeur de sa femme l’aide constamment à le rendre meilleur¸ comme la satisfaction de rendre Claire heureuse est essentielle pour son propre bien-être.

En est-il toujours digne ? Jamie donne libre cours à sa conscience tourmentée alors que le couple à peine retrouvé est contraint de prendre la mer pour sauver P’tit Ian. « Est-ce mal pour moi de t’avoir ? Il murmura. Son visage était blanc comme les os, ses yeux n'étaient plus que de sombres trous dans la pénombre. Je n'arrête pas de penser : est-ce de ma faute ? Ai-je tant péché, te désirant tant, ayant besoin de toi plus que la vie elle-même ? Il est venu, avide de réconfort, et a posé sa tête sur mon épaule » (Chapitre 40¸ T3 Le voyage).

Dès lors¸ il suffit que Claire se montre un tant soit peu distante ou critique pour que les repères salvateurs de Jamie s’effondrent¸ le plongeant dans une détresse totale. C’est le cas lorsqu’ils se sont mutuellement mentis à propos de la bague retrouvée par Brianna et du passage à tabac du pauvre Roger. « Pendant tout ce temps, il s'était cru non seulement seul, mais amèrement reproché par la seule personne qui aurait pu – et dû – lui offrir du réconfort. (…). Je n'arrête pas de penser que Frank Randall était un homme meilleur que moi. Elle le pense. Sa main vacilla, puis se posa sur mon épaule, serrant fort. Je pensais... peut-être que tu ressentais la même chose, Sassenach » (Chapitre 53¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne). Perdre l’estime de Claire est une crainte qui ne s’était plus manifestée depuis le sauvetage de Fort William quand elle lui assénait toutes sortes de noms d’oiseaux¸ « salaud »¸ « chien en rut »¸ « sadique »¸ « enfoiré »…. Etre reconnu dans son exemplarité par sa femme est dès le début de leur histoire une quête intérieure pour Jamie¸ lors des maladroites injonctions à l’obéissance¸ avant que l’amour de Claire libérée de Frank ne lui offre le soutien et la force de poursuivre ses rêves pour qu’il devienne l’homme dont il peut être fier.

Ainsi¸ Claire répare une âme tourmentée par la culpabilité mais l’aide aussi à devenir ce qu’il est : un chef.

Il ne peut prétendre être Laird en Ecosse en raison des poursuites dont il est l’objet mais néanmoins¸ Claire l’aide à se voir comme tel¸ en le confortant dans sa légitime autorité lorsqu’il parlemente avec ses pairs. Qu’il s’agisse de pensées politiques ou de tourments intimes¸ Jamie sonde Claire inlassablement¸ recueille son avis¸ s’entiche de ses conseils¸ réclame son opinion sur les hommes et les événements¸ totalement convaincu de l’intelligence et de l’honnêteté de sa femme pour l’aider à décider au mieux. On la voit à ses côtés mais elle sait s’effacer quand cela est requis, présente mais silencieuse, parfois parce que la misogynie limite son exposition, mais plus souvent par confiance et respect envers un époux dont elle reconnait et admire les qualités de stratège.

Elle comprend parfaitement quand parler ou laisser Jamie prendre le contrôle de la situation et son regard ne se lasse pas de l’admirer : « Voilà un homme qui avait toujours su sa valeur » (Chapitre 12¸ T4 Les tambours de l’automne) et qu’une femme amoureuse sait mettre constamment en lumière. Elle se sent responsable un temps de le voir décliner l’héritage de River Run avant de se rappeler que les convictions qu’elle défend font partie intégrante de la quête de sens que poursuit Jamie¸ tout comme l’épanouissement de celle qu’il aime. Elle s’inquiète de le voir attristé de ne pas disposer d’argent¸ d’un toit et de biens à mettre à la disposition de sa femme mais elle rassure¸ encore et toujours.