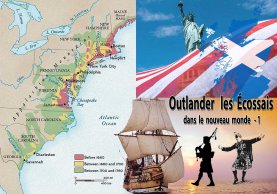

Les Ecossais dans

le Nouveau Monde

Partie 1

"Aucun peuple aussi peu nombreux n'a marqué aussi profondément dans l'histoire du monde que ce que les Écossais ont fait. Aucun peuple n'a un plus grand droit d'être fier de son sang."

James Anthony Froude

Texte : Françoise Rochet

Illustration : Gratianne Garcia

Les Écossais, en particulier les Highlanders, émigrèrent tout au long des siècles.

Ils se sont rendus dans les villes manufacturières d'Angleterre, dans les colonies britanniques des Caraïbes et d'Amérique du Nord et dans les colonies françaises en Amérique du Nord, en Afrique, en Australie.

Ils ont établi des églises, des commerces, des négoces, des boutiques d'artisanat et des écoles dans le monde entier.

Ils firent des tentatives en tant que nation libre afin de posséder leurs propres colonies.

Après 1746, le flux continu d'immigrants écossais a été nourri par des exilés et des sympathisants jacobites.

Les causes humaines de cette émigration étaient nombreuses : le goût de l’aventure, la recherche de nouvelles richesses, les famines, le manque de revenus, l'échec des soulèvements jacobites, les mauvaises récoltes, la confiscations des terres… favorisèrent les départs, involontaires aussi bien que volontaires.

Les retours de soldats Highlanders qui avaient servi en Amérique pendant la Guerre de Sept Ans furent des stimulants pour le départ des Écossais vers les colonies. Après 1763, non seulement des individus, mais des familles entières et des paroisses ont émigré. De nombreux colons prospères ont renvoyé des fonds dans le vieux pays pour permettre aux autres membres du clan de les rejoindre.

Les premiers furent envoyés en mission par le Royaume d’Ecosse tenté par l’acquisition d’une colonie dans le Nouveau Monde. Il y eut plusieurs vaines tentatives qui ne résistèrent pas à la suprématie de la puissante Angleterre. La colonisation écossaise des Amériques consista en un certain nombre d'installations écossaises en Amérique du Nord et d'une colonie à Darién au Panama.

Les Écossais ont donc fait souche en Amérique.

Certains s’y sont retrouvés contraints et forcés, après Culloden, nous le savons.

Voici l’histoire de ceux dont Voltaire disait « Nous nous tournons vers l'Écosse pour trouver toutes nos idées sur la civilisation»

Nouvelle Ecosse (1621)

Les premiers Écossais qui auraient mis le pied dans le Nouveau Monde étaient un homme nommé Haki et une femme nommée Hekja, esclaves appartenant au Viking Leif Eiriksson.

Entre mythe et réalité, la tradition raconte qu’un certain Henry Sinclair, premier comte des Orcades, un noble écossais, aurait exploré l'Amérique du Nord au XVème siècle.

Mais les premiers établissements dont nous possédons des documents se trouvent au Canada, la Nouvelle Ecosse - Nova Scotia en 1621.

Lorsque Jacques VI quitta l’Ecosse pour devenir Jacques Ier d’Angleterre, l’Ecosse n'avait pas encore participé à la grande aventure de la découverte d'outre-mer où l'Angleterre jouait un rôle éminent depuis Elisabeth Ière.

En 1661, il accorda une charte au poète et homme d’Etat William Alexander pour coloniser un territoire situé au sud de l’embouchure du Saint-Laurent et non encore occupé par les Européens et auquel on donna le nom de Nova Scotia.

Au Canada, il se heurta à la fois aux Français et aux Indiens et ne tarda pas à rentrer en Angleterre. Mais il publia un document, « un Encouragement aux colonies » (1625) qui connut un grand succès.

Le nom de Nova Scotia resta à la péninsule où il avait tenté son aventure, avec des toponymes bien écossais tels que Clyde, Tweed, Solway, Forth, Glasgow, qui subsistent jusqu'à nos jours.

Légalement, la charte de la colonie établit que la Nouvelle-Écosse (définie comme toutes les terres entre la Terre-Neuve et la Nouvelle-Angleterre), faisait désormais partie de l'Écosse.

En 1625, Jacques VI rédige une charte pour l'établissement d'une colonie dans la petite île voisine, l’île de Cap Breton. Mais cette terre ne sera pas occupée par les Écossais. Le roi meurt en 1625. Son fils Charles Ier continue le projet canadien.

En 1627 la guerre éclata entre la France et l'Angleterre.

En 1632, sous Charles Ier d'Angleterre, le traité de Saint-Germain-en-Laye fut signé, qui donnait la Nouvelle-Écosse aux Français.

Les Écossais sont donc forcés d’abandonner leur petite colonie.

Souvent considérés comme des Canadiens anglais, les Écossais ont gardé leur identité.

Depuis plus de 200 ans, l'immigration écossaise n’a jamais cessé et est venue enrichir cette nation par tout son savoir-faire. Ces aventuriers du Nouveau Monde étaient des simples paysans, de modestes artisans…

Ils sont devenus des explorateurs, des industriels, des éducateurs, des politiciens, des artistes.

Les Écossais ont contribué à l'évolution du Canada dans de nombreux domaines. Ils sont le troisième groupe en importance au Canada et parmi les premiers européens à s’y être établis.

Lors du recensement canadien de 2016, 4 799 005 Canadiens se déclaraient de souche écossaise, soit 14 % de la population.

East New Jersey (1683)

La province de l'East Jersey et la province du West Jersey, entre 1674 et 1702 étaient deux entités politiques distinctes. Elles ont été fusionnées en 1702. C’est aujourd’hui, l'État américain du New Jersey.

Les Hollandais avaient pris possession du territoire du New Jersey dans les années 1630. Ils s'étaient installés sur la côte occidentale de l'Hudson, en face de l'extrémité de l'île de Manhattan. Ces établissements étaient partie intégrante de la colonie de la Nouvelle-Néerlande, qui incluait également la Nouvelle Amsterdam, qui deviendra New York.

Pendant la Seconde Guerre anglo-néerlandaise, le 27 août 1664, New Amsterdam s'est rendue aux forces anglaises. En effet, face aux Anglais, la Compagnie Néerlandaise des Indes Occidentales ne résista pas. Son but étant le commerce et non la colonisation.

Entre 1664 et 1674, la plupart des colons qui s’emparèrent de l’ancienne colonie hollandaise provenaient de la Nouvelle-Angleterre, de Long Island et des Antilles. Au sud de la rivière Raritan, la parcelle de Monmouth a été développée principalement par des Quakers venus de Long Island.

En 1673, Charles II d'Angleterre donna la colonie hollandaise à son frère (le futur Jacques II).

Il distribua les terres à deux nobles, Sir George de Carteret et Lord John Berkeley de Stratton.

En 1675, East Jersey fut divisé en quatre comtés à des fins administratives : le comté de Bergen, le comté d'Essex, le comté de Middlesex et le comté de Monmouth.

Le 23 novembre 1683, Charles II 'Angleterre accorde une charte pour la colonie de NewJersey à 24 propriétaires, dont 12 Écossais.

La colonie se divise dès lors entre un établissement anglais au West Jersey et un autre, écossais, dans l'East Jersey. Le leader des Écossais était Robert Barclay, un ami de William Penn. Comme lui, il est un Quaker. Il sera le premier gouverneur de l'East Jersey.

Mais il voulait essentiellement privilégier l’influence écossaise dans cette colonie tout en favorisant l’arrivée de ses coreligionnaires qui étaient rejetés des colonies de Nouvelle Angleterre.

La "colonie de l'East Jersey", est établie par un groupe organisé d'éminentes familles écossaises des Lowland. En 1684, la population était estimée à 3 500 personnes dans environ 700 familles (les esclaves africains n'étaient pas inclus).

Ces familles Écossaises, pour l'essentiel d'Aberdeen et de Montrose, avaient émigré volontairement dans l'East Jersey dans les années 1680, dont la moitié en tant qu'engagés. Ces familles étaient arrivées principalement dans le cadre d'une entreprise économique et ne fuyaient pas la persécution ou la pauvreté. Elles avaient des noms écossais : Barclay, Hampton, Craig, Gordon, Stout, Fraser…

Une autre vague, forcée, arriva en 1685, avec l'arrivée des Covenanters, membres du mouvement religieux presbytérien opposé à la monarchie anglicane.

Le Presbytérianisme devint la religion dominante dans les années 1730.

Tous les gouverneurs de l'East Jersey, jusqu'en 1697, furent d'origine écossaise, et les Écossais ont conservé une très grande influence sur la politique et le commerce même après 1702, quand les deux Jersey ont fusionné pour ne faire qu'une seule colonie royale.

En 1682, Barclay et les autres propriétaires écossais ont commencé à développer Perth Amboy en tant que capitale de la province. En 1687, Jacques II a permis le dédouanement des navires à Perth Amboy, donnant ainsi une porte d’entrée aux Ecossais sur le territoire.

Parmi les propriétaires beaucoup d’entre eux n'ont jamais fait le voyage dans la colonie. Ils laissaient la gestion de leurs biens à des superviseurs ou à d'autres membres de la famille. Les plus jeunes fils recevaient souvent des actions dans la colonie afin d’obtenir une position élevée en Écosse en raison des lois sur les successions qui favorisaient les ainés.

Ces fils cadets, ces superviseurs et ces serviteurs sous contrat ont fini par faire souche. Ils fondaient des familles, amélioraient leurs conditions de vie. Ils acquéraient des biens et devenaient des résidents permanents. Au moment de la Révolution, ils seront la bourgeoisie, une nouvelle force vive de la jeune nation.

La majeure partie de cette phase d'immigration a eu lieu entre 1683 et 1700 environ. Après ce temps, il y a eu moins d'arrivées dans la colonie, et les familles qui y vivaient ont commencé à se répandre à l'ouest de Perth Amboy.

En 1702, les propriétaires ont perdu le contrôle direct de la colonie d'East Jersey, qui a ensuite officiellement fusionné avec la colonie anglaise de West Jersey pour devenir la colonie royale du New Jersey.

Cependant les Écossais et les Anglais se considéraient généralement comme culturellement distincts l'un de l'autre, de sorte que chaque ville avait tendance à avoir un caractère écossais ou anglais bien défini. La participation directe de l'Écosse à la colonie d'origine a pris fin dans les années 1760.

À ce moment-là, la plupart des familles propriétaires d'origine avaient vendu leurs propriétés ou étaient simplement retournées en Écosse. En outre, avec le déclenchement de la guerre d'Indépendance, tous ceux qui étaient loyalistes ont été forcés de se battre avec les Anglais ou de fuir.

Monument en l’honneur des Old Scots Graveyard,

Monmouth Co., New Jersey

Quant aux Ecossais patriotes, composés d’une ou deux générations nées dans la colonie du New Jersey, ils étaient prêts à devenir les premiers citoyens des nouveaux États-Unis d'Amérique.

Il nous faut maintenant parler de l’influence des Lumières Écossaises sur l’évolution des idées qui aboutirent à la Guerre d’Indépendance et la création des États-Unis d’Amérique. A cet égard, les Ecossais du New Jersey ont joué un rôle prépondérant et globalement, les Américains ont une dette historique et culturelle envers les penseurs écossais. Les Lumières écossaises sont nées dans les universités d'Édimbourg, Glasgow et Aberdeen qui voulaient améliorer le monde par de nouvelles idées, découvertes et inventions.

Ces philosophes cherchaient à comprendre le monde naturel et l'esprit humain.

Leurs trois principaux domaines de préoccupation étaient la philosophie morale, l'histoire et l'économie.

La « Scottish Enlightenment d’Adam Smith, Thomas Reid, David Hume ont influencé les Pères Fondateurs lors de la rédaction de la Déclaration d'indépendance.

Ils y ont trouvé des principes philosophiques et de nouvelles façons de penser la structure gouvernementale, le développement économique, la relation avec la religion, la promotion de la raison, l'absence d'oppression et les droits naturels.

Les Écossais, cultivés et instruits, ont joué un rôle central dans le développement de l'éducation dans les colonies britanniques. Les Virginiens engageaient essentiellement des tuteurs écossais et la plupart des maîtres et directeurs des écoles des colonies au sud de New York étaient de cette origine.

Ces Ecossais ont rapidement établi des universités, des écoles qui ont joué un rôle fondamental dans l'éducation des futurs dirigeants américains. Par exemple, Thomas Jefferson, John Rutledge, James Madison et Benjamin Rush ont fait leurs études sous influence écossaise.

En 1746, quelques anciens élèves de Harvard et Yale ont fondé le College of New Jersey, qui deviendra plus tard Princeton University. Alors que les premières universités de la colonie, telle celle de Harvard, avaient comme mission de former des ministres du culte, la charte de Princeton était unique. Créée le 22 octobre 1746, elle précisait que "toute personne de quelque confession religieuse que ce soit peut s’y inscrire et assister aux cours. Le but est l'éducation des jeunes dans les langues apprises et dans les arts et sciences libéraux ».

C’est dans ce contexte qu’un Écossais a influencé de près l'éducation, la religion et la politique américaines à l'époque révolutionnaire : le révérend John Witherspoon.

En 1768, cet éminent pédagogue écossais, né en 1723 à Gifford (East Lothian) Scotland, Witherspoon formé à l’université d'Édimbourg, la principale université d'Écosse, est devenu le sixième président du Collège (1768-1794). Il sera plus tard l'un des premiers signataires de la Déclaration d'indépendance. Il a transformé le collège en une institution universitaire moderne, tournée vers l’avenir, qui influencerait les jeunes dirigeants de la génération révolutionnaire.

Il a apporté des changements fondamentaux au programme de philosophie morale et a renforcé les sciences et les mathématiques. Il a élargi et intensifié l'enseignement de la grammaire et de la composition anglaises.

Sous son mandat, le Collège a agrandi ses collections pédagogiques.

De nombreux livres ajoutés à la bibliothèque ont donné accès à un large éventail de littérature contemporaine, y compris des auteurs qui avaient été publiquement contestés.

Des « appareils pédagogiques » pour l'enseignement des sciences (la « philosophie naturelle ») ont été acquis dont le célèbre Rittenhouse Orrery, un planétarium conçu pour représenter les mouvements des planètes autour du soleil.

Princeton - la seule institution presbytérienne dans les colonies - était profondément engagée dans la rébellion. Plusieurs de ses étudiants ont joué un rôle de premier plan.

Elle a produit trois juges de la Cour suprême, de nombreux juges, des hauts fonctionnaires, des membres du Congrès, des sénateurs.

Ses diplômés comprenaient douze gouverneurs, et lorsque l'Assemblée générale de l'Église presbytérienne en Amérique s'est réunie en 1789, 52 des 188 délégués avaient étudié sous Witherspoon.

La philosophie de gouvernement de la plupart de ces hommes était due en grande partie à l'influence de cet Ecossais.

« Ceux qui ne tiennent donc pas compte de la religion et de la sobriété chez les personnes qu'ils envoient à la législature d'un État sont coupables de la plus grande absurdité et paieront bientôt cher pour leur folie. »

John Witherspoon

« Le peuple en général devrait tenir compte du caractère moral de ceux à qui il donne une autorité dans les pouvoirs législatif, exécutive ou judiciaire »

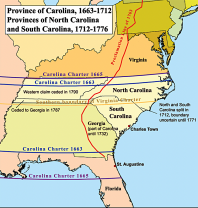

Stuarts Town (1684)

En 1684, deux nobles écossais, Sir John Cochran d'Ochiltree et Sir George Campbell de Cessnock, ont acheté deux comtés en Caroline.

Afin de peupler cette nouvelle région, ils trouvèrent des volontaires parmi les Covenanters écossais, des presbytériens persécutés qui voulaient l'autonomie politique et la liberté de culte.

Bien que fideles au roi, ils refusaient l’emprise de l’Anglicanisme.

Après avoir obtenu des garanties sur leur liberté de conscience et une garantie de gestion autonome sur leur colonie, qui s'étendait de Charles Town (aujourd'hui Charleston) jusqu'aux terres espagnoles les nouveaux colons ont embarqué en mars 1684.

148 colons écossais sont arrivés sur l'emplacement d'anciens établissements français et espagnols, renommé Stuarts Town.

Une fois installés, les conflits commencèrent, tant avec les Amérindiens alliés aux Espagnols et avec les Anglais qui essayaient de revendiquer leur autorité sur les Écossais, ainsi que sur les droits au commerce avec les Amérindiens.

Le site était prometteur, mais Stuarts Town se trouvait à la frontière contestée entre les revendications rivales espagnoles et anglaises. Il était également occupé par plusieurs nations indiennes querelleuses.

Les colons ont négocié une alliance avec une nation locale, les Yamassee, et ont ainsi hérité du conflit continu des Yamasses avec les Timucuans, qui étaient sous protection espagnole. La paix a duré quelques mois, mais en mars 1685, plusieurs Écossais ont accompagné un raid Yamassee contre les Timucuans à Santa Catalina. L'incursion n'a guère gagné plus que quelques esclaves, mais a généré une colère espagnole considérable.

En août 1686, les Espagnols lassés des raids écossais, envoyèrent trois bateaux attaquer Stuarts Town avec 150 hommes et des alliés amérindiens. Affaiblis par la maladie, les Écossais n'avaient que 25 hommes en état de défendre la ville qui tomba. Les Espagnols ont permis aux colons de s'échapper, mais ont pillé la ville avant de la brûler.

Stuart's Town - la première colonie Covenanting - n'a pas été reconstruite.

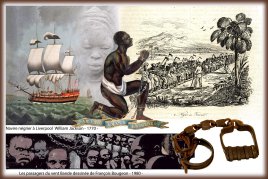

La colonie de Charleston, est devenue au siècle suivant une ville commerciale importante et un grand centre de la traite des Noirs dans les années 1730.

Sullivan's Island, aujourd'hui municipalité autonome et située à l'entrée du port de Charleston, était en effet une porte d'entrée par laquelle transitaient 40 % des esclaves amenés en Amérique du Nord.

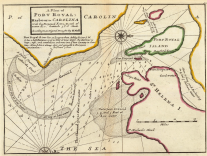

Projet Darién (1695)

Le projet Darién est la tentative coloniale écossaise la plus désastreuse économiquement et politiquement. Dans les années 1690, en concurrence avec les autres puissances européennes, l’Écosse se lance dans un projet colonial de grande envergure à Darién, au Panama.

L’échec de cette entreprise a conduit à l’Union de l’Angleterre et de l’Écosse en 1707.

L'idée de donner aux Écossais une possibilité d'expansion économique outre-mer au moyen d'une compagnie commerciale naquit en 1695, avec un esprit d’autonomie nationale et un espoir dans la conquête du Nouveau Monde. L’intention écossaise était aussi d’entrer en concurrence avec l’Angleterre et l’East India Company, compagnie marchande qui détenait le monopole du marché colonial anglais.

Dans ce projet, il y avait le rêve de voir la réalisation de l’unité nationale par le truchement d’un projet international.

Le blason de la Company of Scotland représente deux hommes de couleur portant des pagnes et affiche l’ambition écossaise avec une devise en latin

Qua panditur orbis

Vis unita fortior :

« Là où le monde s’étend, l’union fait la force ».

L'initiateur du projet était William Patterson, un négociant écossais établi à Londres, qui avait fait fortune en Amérique et comptait parmi les fondateurs de la Banque d'Angleterre en 1694 et de la Banque d'Ecosse en 1695.

En 1695, le Parlement écossais vota la création de la Compagnie d'Ecosse pour le commerce d'Afrique et des Indes (Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies). Elle avait pour mission l'exploration et l'exploitation des pays d'outre-mer.

Mais à la condition que le capital soit réuni !

Là commençaient les difficultés.

L'Ecosse était trop pauvre pour fournir seule tout le capital, fixé d'abord à 350 000 livres sterling, puis élevé à 600 000 livres.

En 1696, les directeurs organisent une levée de fonds afin de financer le projet, tant en Écosse qu’en Angleterre.

Immédiatement, Guillaume III, sous la pression de l’East India Company, s’y oppose.

Cependant, plus de la moitié du capital arriva de l'Angleterre, malgré les protestations des compagnies anglaises.

La campagne de souscription en Écosse est un immense succès : il ne faut pas plus de cinq mois, pour atteindre la somme record de 400 000 livres, alors que l’Ecosse est sévèrement touchée par les guerres et les famines. L’engouement est économique et politique pour les petits propriétaires terriens et les Lairds : l’attrait de posséder des terres, les potentielles retombées économiques pour l’Écosse et la volonté de s’affirmer à l’égale des autres nations européennes sur la scène internationale, notamment par rapport à l’Angleterre.

Un certain Lionel Wafer, médecin-navigateur-explorateur-aventurier-géographe avait visité l'Amérique centrale et fit miroiter aux Écossais les richesses que l'isthme de Darién, entre l'Atlantique et le Pacifique, au sud de l’isthme de Panama, pouvait offrir.

Situé au croisement des routes maritimes, il permettrait de contrôler les communications avec le Pérou espagnol, les Antilles et le Vénézuela.

C’était « la clef de l'univers ». L’ile d’or, la Golden Island.

Si c’était vrai sur les cartes, dans la réalité, le territoire appartenait aux Espagnols.

Mais Wafer affirmait que le Darién n'était pas encore colonisé par les Espagnols et que le territoire était donc, « terra nullius » c'est-à-dire libre pour le premier arrivant.

Cet argument juridique se heurtait aux revendications espagnoles qui réclamaient leur souveraineté sur ces territoires en se justifiant par un siècle de présence dans toute l'Amérique centrale.

Le conflit était donc inévitable.

L'aventure tourna au désastre.

Les colons ont sous-estimé l’importance de cette présence espagnole. Cinq navires avec 1200 colons à leur bord quittent le port de Leith en juillet 1698 et jettent l’ancre à Darién, rebaptisé New Caledonia, en novembre de la même année. Les conditions de vie exécrables sur place – pénurie de vivres, matériel de pêche inadéquat, épidémie de malaria – poussent les colons à fuir en direction de la Jamaïque et de l’Écosse dès juillet 1699.

La nouvelle de l’abandon de la colonie n’arrive pas à temps en Écosse et une seconde expédition atteint la colonie en novembre 1699.

Elle eut plus de succès : un petit commando espagnol fut battu au lieu-dit Tubacanti.

En mars 1700, une nouvelle armée espagnole envoyée en renfort anéantit la colonie écossaise affaiblie par le manque de vivres et les derniers survivants furent emmenés à Séville pour y être jugés conformément aux lois de la guerre et de l'Inquisition.

Les nombreux appels à l’aide à destination de Guillaume III étaient restés sans réponse.

Les Écossais abandonnent définitivement Darién en février 1700.

L’Écosse, qui avait investi d’énormes sommes d’argent dans le projet, se retrouva dans une situation économique très difficile. De suite, l'indignation fut à son comble contre les Espagnols mais surtout contre les Anglais. On accusa le roi d'avoir volontairement saboté le projet de Caledonia et ruiné les espoirs écossais. Ce fut un déchaînement anti-anglais qui alla en s’aggravant.

Le 8 mars 1702, Guillaume d'Orange succomba à la suite d'une chute de cheval.

Anne Stuart, deuxième fille de Jacques VII-II et protestante, fut aussitôt reconnue comme reine tant à Londres qu'à Édimbourg. Anne ne connaissait pas l'Ecosse, mais elle appartenait à la vieille dynastie nationale et elle n'était pas impopulaire. On disait qu’elle gardait des contacts discrets avec son frère le « Prétendant catholique » à Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Il restait une grande question à régler, à savoir la succession de la nouvelle reine.

Si le Prétendant Stuart avait accepté de se convertir au Protestantisme comme beaucoup le lui conseillaient, il aurait sans doute été l’héritier de la couronne mais il s'y refusait. Le Parlement anglais vota donc, le 6 mai 1702, la loi d'Établissement (Act of Settlement) qui assurait la couronne à Sophie de Hanovre, petite-fille de Jacques VI-Ier par sa mère, plus proche parente protestante des Stuart.

Il y avait des risques de voir, à la mort de la reine Anne, les deux royaumes reprendre leur indépendance sous deux souverains différents. C'est l'une des raisons qui ramena au premier plan l'hypothèse d'une union indissoluble des deux pays d’autant plus que l’Ecosse était ruinée.

Le danger de rupture parut assez pressant pour que de part et d'autre de la frontière, il fut décidé que l'union, tant de fois évoquée et tant de fois refusée, était la seule solution efficace, faute de quoi l'Ecosse risquait de se tourner massivement vers le Prétendant Stuart.

En 1706, le moment parut venu de reprendre activement les négociations pour l'Union.

L’Ecosse avait perdu son rêve d’empire colonial. Elle était elle-même devenue une colonie anglaise.

La colonie de Darién fut la dernière entreprise coloniale de l’Écosse en tant que nation indépendante.

Darién en Géorgie (1736)

Le nom de cette ville provient du projet Darién au Panama.

New Inverness ou Darién fut fondée en janvier 1736 par 177 Écossais Catholiques des Highlands (hommes, femmes et enfants) qui fuyaient le conflit entre Jacobites et Hanovriens qui sévissait depuis 1715.

Ces vaillants guerriers écossais, recrutés en tant que colons-soldats par Oglethorpe étaient principalement originaires des environs d'Inverness et se composaient de clans de soutien jacobites dont la majorité ne parlait que le gaélique.

Leur triple rôle était :

* établir une nouvelle colonie ;

* servir de tampon, protéger la Géorgie des Espagnols, des Français et de leurs alliés Indiens ;

* établir rapidement des forts militaires.

Lors de la visite d'Oglethorpe en février, les colons avaient déjà construit une batterie de quatre pièces de canons, construit un poste de garde, un entrepôt, une chapelle et plusieurs huttes individuelles.

Darién a été également aménagé conformément au désormais célèbre plan Oglethorpe.

Ils firent de l'élevage, de l’agriculture et l'abattage des arbres pour survivre.

En 1739, 18 membres de la colonie furent signataires de la première pétition contre l'introduction de l'esclavage en Géorgie en réponse aux habitants de Savannah qui demandaient la levée de l'interdiction de l'esclavage.

La pétition des Highlanders eut quelque succès pendant un certain temps ; l'esclavage ne fut introduit que dix ans plus tard, en 1749 lorsque la colonie se transforma en grandes plantations à l’image de la Virginie.

Ici se termine notre découverte des tentatives du Royaume d’Ecosse de posséder un petit coin de terre dans le Nouveau Monde. Dans le prochain chapitre, nous verrons dans le détail qui étaient ces Ecossais qui tentèrent l’aventure du Nouveau Monde et leur impact sur la société américaine au fil du temps.

« – Nous sommes rassemblés ici pour accueillir nos vieux amis et en rencontrer de nouveaux, dans l’espoir qu’ils se joindront à nous pour bâtir une nouvelle vie dans un nouveau monde. »

Jamie Fraser

T 5 CH 5

Bibliograhie

BERENGER Jean, DURAND Yves, MEYER Jean, Paris, Pionniers et Colons en Amérique du Nord, Armand Colin, 1974

BERNANT Carmen, GRUZINSKI Serge, Histoire du Nouveau-Monde: Les métissages, Paris, Fayard, lieu, 1993

BORSTIN Daniel, Histoire des Américains, Robert Laffont, Paris, 2003

DICKISON John, MAHN-LOT Marianne, 1492-1992 Les Européens découvrent l'Amérique,

Lyon, Presses Universitaires de Lyon, 1991

HEFFER Jean, WEIL François (Dir), Chantiers d'histoire américaine, Paris, Belin, 1994

KASPI, André, Les Américains, I. Naissance et essor des Etats-Unis 1607-1945, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1986

MEYER Jean, L'Europe et la Conquête du Monde, XVIe-XVIIIe siècle, Armand Colon, Paris, (1ère éd 1975), 1990

OUELLET Réal, La Relation de voyage en Amérique (XVIe-XVIIe), Au carrefour des genres, Laval, Editions du Cirel, Les Presses de l’université, 2010

TROCMÉ Hélène, ROVET Jeanine, Naissance de l'Amérique moderne XVIe-XIXe siècle, Paris, Hachette Livre, 1997.